In Bride Street in Dublin’s Liberties, one of the most curious incidents of Irish planning history has recently repeated itself. The striking 1970s brutalist facade of the former headquarters of architectural practice Stephenson Gibney + Associates has been retained, while the remnants of a much-storied eighteenth and nineteenth century structure which formed a part of the same building, have been quietly demolished. In its place will be a significant new hotel, which uses the retained near-fifty-year-old facade as a contextual umbilical to the past – an arts themed relic. While the redevelopment of this site for a demonstrably more public use is certainly welcome, the brick shell will now have a merely tenuous connection to the new.

When Stephenson Gibney + Associates acquired the old Molyneux Chapel on Bride Street in 1971, their clients and collaborators must have thought they had lost the plot. Impacted by generational poverty, planning neglect, and demolition as a result of Dublin Corporation’s road-building efforts, it must have been a considerable cultural shock for the practice and its staff, moving from leafy Dublin 6 where the studio had been spread out over three separate Victorian properties, on the site of what became the practice’s Fitzwilliam Lawn Tennis Club in 1973. But like knights charging into a windmill bedecked landscape, Sam and Arthur clearly saw this approach as a way of spearheading a new colonisation of the city centre, which would inspire others into the same action, reclaiming one of the most historic parts of Dublin for makers and creators. And of course, it was reasonably cheap [1].

But what kind of practice was it, with the ambition and confidence to propose colonising this historic part of the city, with the buccaneering gumption, and not least the funds to do so? Sam was born at 80 Manor Street in Stoneybatter in 1933, while Arthur from Fairview, was a year older. They were almost exact contemporaries of the Anglo-Italian architect Richard Rogers and his one-time partner, Norman Foster. It’s remarkable to think that Sam and Arthur’s practice was substantially more accomplished, and certainly much larger at an earlier date, than the offices of these later titans of British hi-tech. By the early 1970s, when Norman Foster and Richard Rogers had dissolved their partnership of Team 4, the high-flying Stephenson Gibney Associates had completed the ESB buildings on Fitzwilliam Street, won in international competition, and were in the midst of design work on the Central Bank, the enormous Agriculture House on Kildare Street, the beautiful School of Theoretical Physics on Burlington Road, and projects in London and Brussels, as well as working on their custom-designed offices with space to accommodate a team of 130 staff.

At the same time as the practice were completing Molyneux House, it was also concluding one of its more controversial developments on Hume Street near St Stephen’s Green. Having originally gained consent for a series of modernist office blocks, the practice was forced by public outcry over the loss of historic Georgian fabric, via government intervention, to amend the design to incorporate a Georgian pastiche facade. Stephenson lamented this approach as an architectural response in a historic cityscape, declaring it in Hibernia Magazine “a misguided Solomon’s judgement”, opening the door for anything to happen, as long as the external image of apparent streetscape continuity was maintained. His words would prove remarkably prophetic.

Designed as a striking statement of intent, in a vigorous transatlantic style which referenced exemplars like Louis Kahn, John Carl Warnecke and Hugh Stubbins, the facade of heavily modelled brickwork extends about three metres in front of the existing frontage, which is retained, entombed in a brick skin. It is a remarkable brutalist essay in hard wire-cut textured masonry, carefully relating to the spaces formed between it and the gothic curiosity of the existing chapel. The facade itself was shockingly modern – aggressively so, even. Like an elaborate billboard, it heralded a world decidedly exotic, science-fiction like, most excitingly of all, American. A place where people in tan suits with wide lapels, even wider ties, and moustaches à la mode, were manufacturing a new Ireland through a haze of Rothmans' smoke, echoed in the bronze tint of the floor-to-ceiling frameless glazing. This stylish stretched veneer of modernity over the more prosaic historic backdrop, incorporated a stained-glass window spanning the first and second floors, preserved in situ as a relic behind the brick screen. The strength of this elevation as corporate identity clearly made signage superfluous. Only a small limestone tablet, insert into the Bride Street frontage, provided the name – Molyneux House – in vaguely Gothic lettering.

Much more nuanced than often credited, the facade treatment extended downward into a carpet of pavement finish, and smaller protective pyramidal forms, a kind of undulated brick carpet which remade the street edge robustly, terminating with a single specimen tree planted in the protective niche formed to the adjacent Victorian houses. The entrance sequence, lost in 2001 in favour of a car park, must have been a dramatic, even flamboyant space. Entering via a narrow passage between towering flanks of brickwork, with the obligatory chamfered corners and parapets so redolent of the period, the visitor entered a release space protected from the harsh environment outside. It was filled with a feature planting scheme and a waterfall, enlivened by the play of light entering from the west. Even the adjoining perimeter party walls were finished a textured brown render, colour matched to the ubiquitous brick finishes which continued unbroken from courtyard into the reception space adjacent. A remarkable introduction and one of the most extraordinarily theatrical spaces ever designed by an architect for their own use.

It couldn’t last, of course. By 1974, a collapse in the property market had already impacted on the work of the practice, eroding the kind of projects that had kept it so busy over the previous fifteen years. This pre-empted Arthur’s departure from the partnership in 1976, keen to practice in a smaller organisation, leaving – according to Sam – on the same good terms that they started together. The construction of Canon Court, across Bride Street, obscured the view of the cathedral from the upper ‘periscope’ viewing room, decontextualising the reason for the facade. In the 1980s, Sam moved much of his practice to work on London-based projects from both Dublin and a new base in London, having arranged a merger with commercial architectural practice Stone Toms. Another downturn in the early 90s in London, resulting in the sale of the building, provided the impetus for a new owner to erode the key components of the original, in search of more standard spaces. The process of denuding the qualities of the original work, had already begun.

Molyneux House represented a particular time in Irish architecture, reflecting the vigorous confidence of a brave new republic full of the optimism of the times, before the first vestiges of the energy and environmental crises of the 1970s closed the door on this period. As a bespoke environment for an architectural practice, it was absolutely unique in the country, with a facade albeit skin-deep, boldly proclaiming brutalist modernity.

In a world of city planning increasingly obsessed with the value of image as opposed to content, how do we decide what to protect? This is a particularly difficult question, given modern architecture’s supposed ambivalence to context, in contrast to the gentle formalism of classicism, which ensures that individual buildings are less important than the effect of the unified streetscape – despite being what Sir John Summerson described in the Georgian Society Bulletin as “simply one damned house after another” [2]. In addition to the obvious imperative for retaining carbon-rich structures for new uses, the bluntness of our Protected Structure system will need to be better refined, to allow status to be conferred on particular building elements of significance, rather than on a blanket basis. In the case of Molyneux House, perhaps the most humane thing would have been to allow it to go, rather than endure a slower, undignified demise.

In contrast with the theatre of practice it once contained, it is now sadly a pantomime mask. The personages behind the facade, along with their pioneering spirit, are long gone.

Future Reference is supported by the Arts Council through the Architecture Project Award Round 2 2022.

1. £60,000 bought the shell and site of the old Molyneux Chapel, which had previously been converted into a recreation hall for the nearby Jacobs biscuit factory. Before this, the building had an auspicious history, adjoining the site of Molyneux House to the south, and being constructed as equestrian performer Philip Astley’s Amphitheatre of Horsemanship in 1788. After the Act of Union, it became a theatre, before being converted to religious use as part of an asylum for blind females housed in Molyneux House, in turn demolished in 1947. It was this storied yet crumbling shell which the practice acquired as the skeleton of a consolidated headquarters in 1971.

2. Modern architecture at mid-century was – with few exceptions – unconcerned with issues of streetscape and continuity, preferring the ideal of the isolated object building, set in stark contrast to traditional urbanism. As the postmodern architect Robert AM Stern has noted, the Seagram Building in Manhattan is magnificent in its more traditional urban context; but ten Seagram’s in a row?

McCormack’s was established in 1984, its current owner is Daire O’Flaherty. At only 18m2, this shop had a powerful presence. It poured out onto the footpath with negotiations of punctures, pedals, pumps, prices, all conducted in the plein air of Dublin's Appian way: Dorset Street. Pronounced in dublin-ese with two distinctly independent syllables: Dor-set, the common pronunciation is miles from the English variant, and lightyears from the ancient route it is descended from: Slige Midluachra [1].

Unlike the case of the ill-fated Delaney’s bike shop in Harold’s Cross, allegedly Dublin’s oldest [2], it was not the increasing cost of business that shut McCormack’s. Right up to its closure, this institution was hopping, with a lively mix of locals and commuters dropping by. According to the shop owner, it was closed because the landowner valued the site more highly once it was vacant [3].

The bike shop was part of a three-storey suite of early Victorian buildings, with a modified-Georgian terrace lining the west of it. Over the past few years its neighbouring buildings have similarly been drained of residential and retail tenants. Relatively recently this city block was home to a multitude of residents and traders. Today the signature calling card of vacancy is visible: permanently-opened windows in the upstairs accommodation, allowing the elements in. Nobody lives or works here to shut them, to provide essential daily care for the properties.

Daire is well-versed and articulate in what makes a city both at the ground level and also the urban theory behind it. On Dorset street, he had a frontline view of Dublin’s traffic congestion during the morning rush hour, the worst it has ever been. He sees an opportunity in the widespread overhaul of the city’s transport system, which is being redesigned to prioritise public transport for decarbonisation and public health: more and more people are choosing bikes to get into work, and live healthily in the city. In his view bikes are a key component of any liveable city, like Paris or Amsterdam perhaps. What good will the ambition to encourage cycling be, without centrally-located facilities for bike repair and maintenance? It is akin to building a motorway without including for new garages or fuel stations.

McCormack’s now has a premises in Drumcondra, not far from its former home. Daire has yet to establish whether business has actually improved. However the same lack of protection exists in the new premises. While there are limitations to hosting a bike shop in a small retail unit (cycling shops are ideally suited to larger premises), McCormack’s 41 years of business clearly evidences the ability to adapt and survive in small, tight spaces. Shutting small independent retailers down will make larger out of town suburban shops more tempting to customers. It also offloads a responsibility to repair the existing urban fabric – an essential and under-practised aspect of the circular economy.

At a municipal level, there are no obvious consequences for ousting an established small business tenant in pursuit of greater profit, nor any meaningful incentives for landlords to help their continued operation. The desire to sell off buildings with a clean slate of no sitting tenants is widespread in Dublin, and the results are most keenly felt by the communities who make use of small businesses.

The closure of specialised small businesses, like bike shops, locksmiths, butchers, grocers, are part of a broader list of fatalities to our city, with the loss of art and cultural spaces, pubs and restaurants regularly causing public outcry. In an ecosystem of property speculation, few tenancies are safe. The liveable city we aspire to is increasingly precarious.

While these changes can seem inevitable and often happen stealthily over time, the failure of policy to protect small independent businesses will cost the city in easily-measurable ways. Daire famously once broke up a fight between two locals arguing over money; he, and many others like him, are eyes, ears and a friend to the street. This is increasingly relevant when the media and political debate focus on inner-city crime and public safety.

The fight for the city is not just in art spaces, pubs, heritage properties, it is the fight to protect small independent retailers and those committed to living and doing business in our city. If Dublin is to stay open for business, it has to protect them too. If indeed ‘we are Dublin Town’ let us aim to be like Paris or Berlin, with a feast of small independent retailers providing vibrancy to streets [4]. Task forces looking at the bigger picture of our urban centre, encouraging external investment in the city, need to be clear-eyed on the draining of its smaller, but equally essential, tenants. Otherwise fixing the city through grand gestures will be like trying to save a marriage, while having an affair.

After forty-one years in business, what was probably Dublin’s smallest bike shop: McCormack’s on Dorset Street, pulled down the shutters for the last time. In this article, Róisín Murphy uses the closure as a lens on the wider disappearance of small, long-standing businesses from the city, asking how liveable Dublin can remain if independent traders and venues continue to vanish.

Read

This year’s presidential election made visible a dynamic that is often overlooked in political analysis: how campaigns operate as a form of civic infrastructure, and to what extent design plays a role in their efficacy. Far from being peripheral or decorative, the visual strategies deployed by candidates’ structure how people encounter political life; they shape perceptions long before policy is discussed or manifestos are read. Political design occupies a unique position within democracies, somewhere at the intersection of communication, civic identity, and public trust.

In Ireland, this relationship between design and democratic expression has been strained by a decades-long pattern of executive neglect. Successive governments have systematically deprioritised design and aesthetic quality in public communication and built infrastructure. Senior ministers increasingly frame design as an optional consideration, an unnecessary add-on rather than a fundamental part of how the State articulates care, competence, and regard for its people. As Minister for Public Expenditure Jack Chambers stated during a debate concerning escalating costs at the National Children’s Hospital (NCH), ‘there needs to be much better discipline in cost effectiveness… That means making choices around cost and efficiency over design standards and aesthetics in some instances’ [1].

This position, widely cited and contested, exemplifies a broader ideological shift which sees design treated as a dispensable luxury rather than an essential civic tool [2].This framing misunderstands the function of design within public life. Design, in this case, is not ornamental; it is a mode of communication through which the State makes itself legible. When design is neglected, the consequences extend far beyond the aesthetic and shape the conditions under which political meaning, public trust, and civic visibility are formed.

In the aftermath of Catherine Connolly's election as President, commentators highlighted the design and visual expression of each candidate as decisive factors [3]. Connolly’s campaign offered me a rare opportunity to explore what an authentically Irish political visual identity might look like when grounded in cultural memory rather than branding for the sake of visuals alone. While designing, I drew directly from Ireland’s vernacular signwriting tradition: the hand-painted shopfronts, gilded fascias, and serifed letterforms that once defined the visual texture of towns and villages. These were not simply aesthetic references. They embodied authorship, locality, and a sense of civic care.

By incorporating hand-drawn lettering, a deep green and cream palette, and a postage-stamp motif, the campaign sought to restore the tactile warmth and humanity often lost in contemporary political design. The stamp, a quiet symbol of communication and exchange, is a reminder that politics is, at its core, a conversation carried between people. This concept frames Irish craft traditions not as relics, but as living cultural practices capable of shaping contemporary civic discourse.

In doing so, Connolly’s campaign made design itself an act of cultural continuity, a way of honouring the past while proposing a more grounded and participatory future. By the time Connolly declared on election night, “This win is not for me, but for us,” the sentiment had already been woven through posters, leaflets, and social media, a visual testament to a campaign that made the collective visible long before the votes were counted [4].

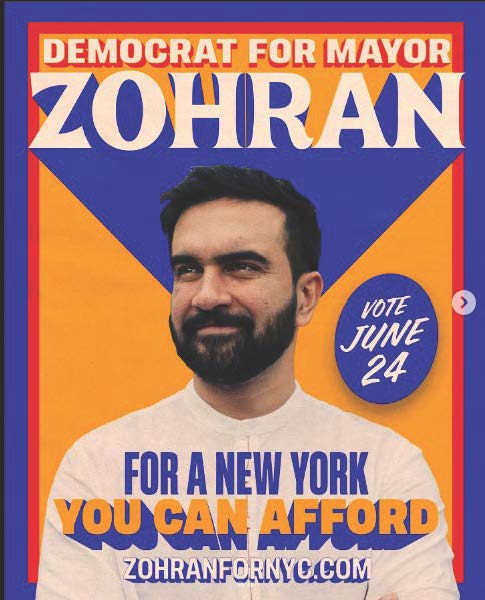

Across the Atlantic, Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral campaign in New York City attracted attention first for his democratic socialist views. It was the striking coherence of his campaign design, however, that propelled him into broader public discourse. Not since Shepard Fairey’s Hope poster, for Barack Obama, had a political image circulated so widely. It gained the kind of immediate recognition associated with Jim Fitzpatrick’s image of Che Guevara.

The Mamdani campaign was intentionally rooted in the material and cultural vernacular of the city itself. The cobalt blue and yellow palette was drawn directly from everyday sights in New York: bodega awnings, taxi cabs, MetroCards, hot dog vendors, and the signage of small independent businesses [5]. In this way, the campaign aligned itself with working-class infrastructure that defines the city’s public life, situating Mamdani not as an outsider but as a candidate embedded in the city’s social, cultural and economic rhythms [6]. Central to this strategy was the premise that design could serve as a communicative bridge to the constituency Mamdani sought to represent. In doing so, the campaign framed visual culture as a mode of continuity and care, a reminder that political communication can affirm belonging as powerfully as it persuades.

Irish election materials, as well as the State's political design more generally, don't attempt to convey substantive meaning through visuals. Their long-standing reliance on formulaic portraiture, generic slogans, and minimal graphic refinement mirrors a broader campaign strategy in which candidates are packaged as approachable local figures using highly-conventionalised visual cues. This approach reduces design to a mechanism for name recall rather than a vehicle for articulating political values or fostering civic engagement. The environmental waste associated with poster production only heightens the sense of outdatedness and underscores how Irish campaign materials often lag behind the more considered, narrative-driven strategies emerging elsewhere. As such, this tradition of visual identity crystallises the limitations of Irish political branding: a dependence on repetition, familiarity, and low-risk aesthetics at the expense of meaningful visual communication.

A strong democracy depends on sustained, accessible dialogue between the State and its people. Visual identity is structurally embedded within this exchange. Visual languages that are familiar or culturally resonant reduce cognitive load and strengthen affective engagement, whereas generic or stylistically flattened forms tend to weaken meaning-making [7]. In this sense, campaign aesthetics function as a form of civic infrastructure, shaping perceptions of authority, intention, and legitimacy before a single word is spoken.

When design is framed as a luxury rather than an essential component of civic life, it erodes the shared visual language through which democratic communication occurs. Such an approach initiates a feedback loop. Minimal investment in design yields fewer meaningful symbolic or material expressions of public life. As these expressions diminish, the State becomes increasingly illegible to its people. Over time, the corporeal presence of the State, its visibility in the everyday, degrades. What was once a free-flowing dialogue becomes generic, flattened, and emotionally inert. Political branding therefore mirrors the State’s broader orientation toward public infrastructure. When design is treated as secondary, a dispensable aesthetic layer rather than a civic medium, its communicative and democratic potential collapses. When taken seriously, however, design becomes a point at which cultural belonging, political intent, and civic participation converge.

Ireland’s future civic health depends not on dispensing with design but on recognising it as a central component of public life. It is the medium through which the State becomes visible, legible, and trustworthy.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Highly visible and emotionally charged, electoral campaigns are often the first instance in which a state’s people encounter their elected representatives. In this article, Anna Cassidy, designer for Catherine Connolly's presidential campaign, examines how political design is indispensable to the democratic process.

Read

“[W]asn't this all started by some terminally online moron in trinity? … Nobody gives a shite so long as the statue isn't actually being damaged” wrote [Deleted] on the reddit page r/Ireland in a thread to discuss Dublin City Council's proposals to stop the repeated groping of the Molly Malone statue on Suffolk Street — her breasts repeatedly touched by the sweaty hands of tourists, so much so that the dark patina has been worn away to reveal the earthy metallic dark orange of the bronze from which the mythical fishwife was cast. Thousands of images of Molly #mollymalone circulate on TikTok. A group of men dressed in Jack Chalton-era Irish football jerseys stand in line to rub their faces in her breasts. In the comments section one user posts, “reminder she’s 15 in this statue,” others disagree, claiming she was older, as if somehow the behaviour would be permissible if the statue represented Molly as 17 – the legal age for consenting sexual acts. Others use the platform to protest the behaviour.

If you ask Google’s AI Gemini about the practice, it tells you that “this practice is now discouraged by authorities for preservation reasons.” This is artificial stupidity, a view blind to a far more important problem, one that philosopher Sylvia Wynter described as an urban planning that assumes the male-coded subject as the norm, while others—women, Black, Indigenous, and colonised peoples – are excluded, marginalised, or rendered invisible [1]. For Wynter, urban space is ontologically male, in that its logics of design, governance, and belonging reproduce a gendered and racialised “Man” as the universal standard of being. Speaking to RTÉ Radio One, DCC Arts Officer Ray Yeates (a man) suggested that one solution could be to “just accept that this behaviour is something that occurs worldwide with statues” – human stupidity [2]. Perhaps Yeates might agree to a plaque being added, inscribed with a quote from Wynter: “Man …overrepresents itself as if it were the human itself”[3].

As images of the statue circulate online, they both promote and raise awareness of this deleterious practice. But this is the means and not the end of their circulation. These images turn Suffolk Street into a space for the production of a strange kind of economic exchange. With one sweaty hand on a breast, and the other on a smartphone, tourists become workers. Here, as in all of everyday life, a distinction can no longer be made between work and play. In our age of contemporary digital technology all of everyday life is a factory. To play is to work; the digital proletariat; to use a technological prosthesis is to be used by that prosthesis. These interfaces, designed for the many by and for the benefit of the few, manage life by means of ‘fun’. Spaces like Suffolk Street are, as Letizia Chiappini writes, where “[a]ffect, desire, pain, and love, are digitally mobilised for direct spatial impact” [4].

Henri Lefebvre called this abstract space – “[t]he predominance of the visual (or more precisely of the geometric-visual-spatial)” [5]. He described this kind of logic as a planetary mesh that has been thrown over all space [6]. Any space, anything, anywhere, no matter how banal is subject to this logic. 13,461 km away from the Molly Malone statue is an underpass in the Chinese city of Guilin. Each night crowds of outdoor live streamers gather to steam content on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), their faces glowing in the phosphorus white of selfie lamps. Geolocation means that if they are closer to more prosperous neighbourhoods then they make more money from the wealthy clients who live there. These leftover urban spaces that are seen as unattractive and once disregarded in a capitalist economy have become spaces where new economies and ways of working emerge. I have written elsewhere about the disproportionate role that Ireland plays in facilitating the infrastructures that produce these kinds of spaces [7]. This is a new kind of geopolitics, one facilitated by State fiscal policies, such as in Ireland, home of one of lowest standard corporate tax rates in the EU.

This is capitalism incarnate – capitalism become flesh. Everything has an exchange value. There is not a thing that cannot be transformed into a commodity to be circulated in an economy of flesh, thoughts, drives and desires. This is an economy governed by images, subject to what legal scholar Antoinette Rouvroy calls algorithmic governance – the governance of “the social world that is based on the algorithmic processing of big data sets rather than on politics, law, and social norms” [8]. The statue of Molly is a public surface subject to an extractive logic, via the lens she is engineered for constant circulation, interaction, and capture. The statue as code has her meaning flattened into content for the purpose of data extraction and ad revenue. This kind of collapsing together of work and leisure is a weapon of mass distraction. It removes us from everyday life, producing what philosopher Henri Lefebvre called a “transcendental contempt for the real” [9].

Lefebvre also called for a right to the city, by which he meant the right to the production of truly democratic space. Space that is not subject to capitalist abstraction. To what extent this is even possible in our precarious age of algorithmic governance is questionable - but nonetheless we must seek to understand, hope and act.

The groping of the Molly Malone in Dublin reveals a complex new urban condition – the algorithmic production of space. Social media, viral images, new modes of capitalist production, foreground the emergence of an entirely new logic of spatial production. What does this mean for the possibility of a right to the city?

ReadWebsite by Good as Gold.