Recent developments in urban design discourse in Ireland include an Urban Design Symposium at UCD in 2023 [1], during which proposals to pursue an accreditation for urban designers within the RIAI were discussed. While the Symposium’s published proceedings highlight Irish architecture’s broad professional commitments, any meaningful engagement with environmental or climate adaptation issues were glaringly absent.

While it is too easy to point fingers and add to the rhetoric and calls for further expansion to the architect’s professional activities, the issue as I see it is rather that the profession of landscape architecture within Ireland remains critically underdeveloped. Elsewhere landscape architects are leading on large-scale urban adaptation projects and clearly articulating their role in the compounding climate and biodiversity crises. The urgent need for such professionals has led some of the western world’s most prized schools of architecture – the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL; ETH Zurich; Pratt Institute – to inaugurate new professional programmes in landscape architecture in the past six years. To highlight the excitement and optimism that exists amongst its practitioners, Belgian landscape architect Bas Smets recently said that he was drawn to the field because “there’s still so many things to be invented" [2]. Landscape architecture, in other words, is finally having its moment.

In this regard I wish to discuss the disciplinary formations and practices of landscape architecture which are relevant to the development of urban design in Ireland. I frame landscape architecture here in its most ambitious form as it intersects with processes of urbanisation and as it emerges as a field uniquely equipped to take on a diverse range of issues at the intersection of living systems, public space, and social injustices. I also argue that the landscape architect has as much of a claim today to lead on urban design projects as the architect, and that ongoing considerations to accredit architects as urban designers by the RIAI may end up excluding landscape architects from their work to adapt the city to the environmental and social challenges of the twenty-first century.

Greater cultural awareness of the climate and ecological crises alongside an emerging consciousness of spatial injustices has positioned landscape architects as primary agents in the design of the built environment. This has perhaps been best articulated by Charles Waldheim in his 2016 publication Landscape as Urbanism, where he argues that traditional urban planning and design strategies – allied with the field of architecture – are incapable of reconciling with the pace and scale of urban change caused by both deindustrialization and market-driven urbanisation. As industry recedes from urban centres it is typically met with an inflow of global capital to capture opportunities for the making of buildings as financial machines. When the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey announced the sale of Brooklyn’s abandoned waterfront piers in the 1980s, plans to occupy the 1.3-mile waterfront with fourteen-storey apartment buildings quickly emerged, but community groups challenged such developments and mobilised political and financial support for the project that would become Brooklyn Bridge Park. Over twenty years, the planning and design of the 85-acre park was led by landscape architects Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA), and since 2021 has provided contact with the waterfront, access to an array of outdoor programming from sports fields to moments of solitude, offered open space to diverse communities, and acts as a bulwark to worsening storm surges. Brooklyn Bridge Park is a masterful choreography of expansive and intimate public space, curated views, play opportunities, and a thickening weave of volumetric plant and landscape material that is everywhere missing from cities.

While urban design and development typically limits the biophysical world to remaining parcels of open space, at Brooklyn Bridge Park this pattern is overturned. MVVA worked with economic planners to calculate the annual maintenance costs for the landscape – providing the logic for the volume of building development along its edges that would directly finance the park through property taxes. The subversion of architecture to landscape architecture in this case of urban development is instructive in longstanding debates over which design disciplines have the authority to guide decisions on the formation of the city. Yet the moment we find ourselves in – global heating, ecosystem devastation, landscape contamination, coastal vulnerability, stormwater pollutants, spatialised social inequities – requires a new kind of design intelligence led by the logic of landscape. While disciplinary formation in the design and planning professions mean that landscape architecture enjoys little public awareness or professional authority in Ireland, across the world landscape architects are leading on infrastructural urban design projects that are absorbing the shocks of these crises at the intersection of urban and living systems.

An unspoken premise within urban design discourse is often that the work of landscape architects is responsible for unmooring architectural quality from urban space. To be sure, there are endless examples of poorly executed work by landscape architects, just as there are from architects. Yet for prominent architect and urban designer Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, the emergence of landscape architecture in recent decades from within parks and gardens – at least where he is looking – into streets and the rest of the urban fabric has resulted in his call for a total abandonment of landscape in the city: “If we want to respect and preserve nature, we must not confuse it or mix it up with the city … The city must withdraw into its own space, develop distinct boundaries and concentrate on itself, becoming dense, solid and as hard as stone" [3]. Lampugnani’s admiration for the historic Italianate urban fabric and the writings of Aldo Rossi have caused conceptual upset and led to the reasoning that denser and harder cities mean more space for nature in the hinterlands. But cities are not closed systems.

Landscape urbanism is being internationally embraced in the discourse of urban design to organise the urban fabric around biophysical systems. Yet discursive formations of urban design in Ireland, at least as suggested by the recent Research, Discipline, and Practice: UCD Urban Design Symposium 2023 seem to consider landscape only in its pictorial dimension. For example, in the symposium’s published proceedings the only engagement with a landscape framework is by Finola O’Kane. Here it is engaged as a “landscape perspective” (or viewshed) comparison of Irish town squares using late nineteenth century photography with more recent equivalents. O’Kane’s lesson is that both incidental developments that have taken place in town squares – such as at Moville, Co. Donegal – and deliberate design attempts – such as at Eyre Square in Galway – are both responsible for “the loss of significance in urban space" [4]. The historical photographs certainly attest to the existence of a kind of character which Irish architects are perennially preoccupied with. Yet these historical examples show either acres of sealed ground or lawn with trees as framing mechanisms. In other words, these spaces are highly impoverished biophysically, and while this may seem to be less of a concern in very small rural towns where opportunities may be more widely available to slow down and remediate surface water pollutants and capture airborne particulates through green infrastructure – these areas are increasingly inundated with water from more frequent storm surges and fewer opportunities to slow and absorb water upstream. These examples may be even less appropriate as visions for our urban future in Ireland’s larger towns and expanding cities.

The project of the city in the twenty-first century will need to reformulate urban conceptions of character and aesthetics to grapple with compounding environmental and social pressures. Core to this project will require engaging plant and landscape material as figures in the urban fabric as they encounter and mobilize landscapes’ logic. Such a reorientation however is likely to prove challenging as they have historically featured as backdrop, framing, or embellishment to architectural logic and form. Compounding this challenge is the identification in recent decades of the complex phenomenon of “plant blindness” in Western society - that is the failure to notice or account for plants in daily life [5]. Although there are many theories that aim to account for landscape architecture’s inferior position in the design and planning fields, perhaps its association with plants which evolved to “avoid recognition” is perhaps one of the more compelling versions. Yet the collaborative endeavour with plants, soils, and water, mark landscape architects as the primary design experts working at the intersection of the built environment and living systems and such professional commitments are a critical contribution to leading the development of the twenty-first century city.

I am sometimes asked whether architects can also do landscape architecture. Can landscape architects also make buildings? Prominent American landscape architect James Rose did design both gardens and houses for his clients. And if trained architects seek to become landscape architects through practice, then more power to them. But as design professionals operate in increasingly complex global conditions, I think we need to clarify the core knowledge of our fields and the relative value of those contributions to the built and unbuilt environment. Current discussions to provide an urban design accreditation for architects calls for broader conversations about what constitutes expertise in urban design, and how such accreditation would affect other built environment professionals who have as much of a claim to this work as architects. While the proceedings to the UCD Urban Design Symposium showed balanced views on who should be involved in urban design projects, some fervently advocated for this role to be led by architects. From where I stand, urban design constitutes a broadly interdisciplinary domain – it is hubris to suggest that the range of challenges which emerge here could only be uniquely led by architects. If the end goal is to design environmentally resilient, socially just, and beautiful Irish towns and cities – rather than to, as Matthew Carmona argues in the Symposium’s proceedings, “grab the territory professionally and define its limits through accreditation” [6] – then interdisciplinary venues to advance this project should be pursued. As landscape architecture slowly emerges as a profession and area of intellectual enquiry in Ireland, architects should embrace its possibilities for Irish cities, work to include landscape architects in urban design’s discursive developments, and support its emergence in the academy.

Open Space is supported by the Arts Council through the Arts Grant Funding Award 2024.

1. Michael Hayes and Alan Mee (eds.), Research, Discipline, and Practice: UCD Urban Design Symposium 2023, Dublin, Type, 2024.

2. Bas Smets, "Nature Design," Harvard Magazine, July 5, 2023.

3. Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, "Cities are Not Landscapes", Domus, July 2020.

4. Finola O'Kane, "A Very Short History of Urban Design in Ireland or Classic Irish Towns of Middle Size", Research, Discipline, and Practice: UCD Urban Design Symposium 2023, Dublin, Type, 2024, p. 19.

5. Ainara Achurra, "Plant Blindness: A Focus on its Biological Basis", Frontiers in Education 7, 2022.

6. Matthew Carmona, "Urban Design, No Boundaries", Research, Discipline, and Practice: UCD Urban Design Symposium 2023, Dublin, Type, 2024, p. 46.

Most people call it crypto but for the purposes of this exercise we’ll use the term "blockchain".

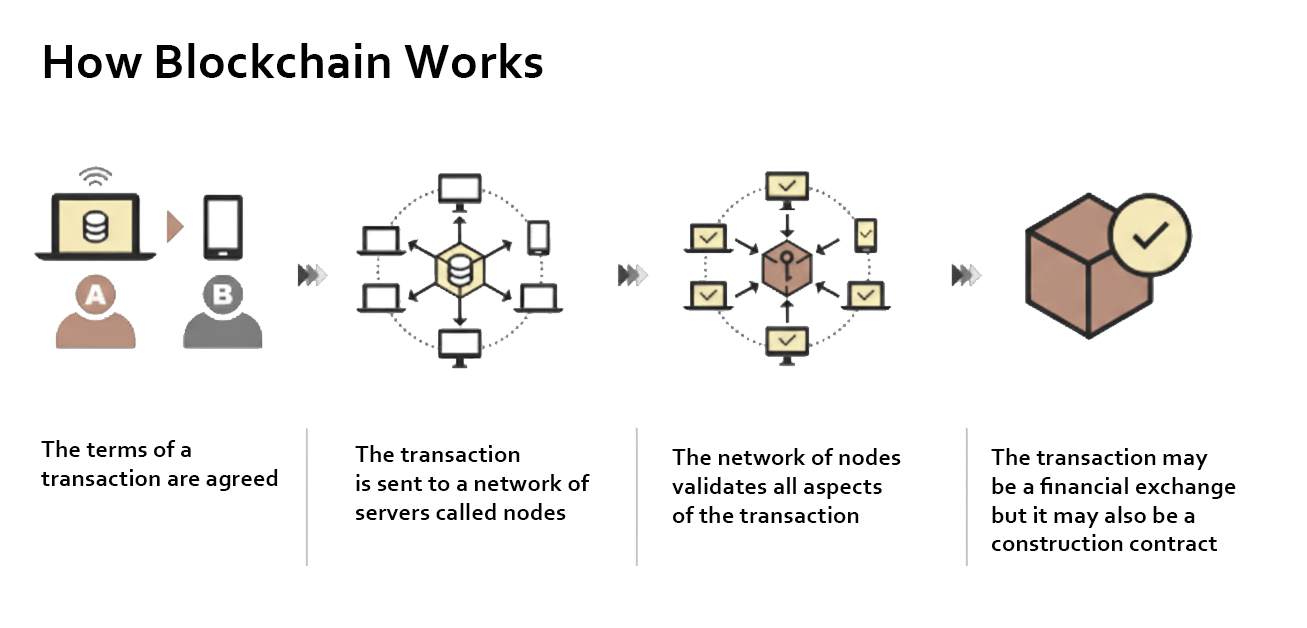

At its core, a blockchain is simply a way of recording an event on a digital ledger instead of in a paper document. This could, for example, be a record of an agreement - the kind of agreement people have been making between one another for as long as agreements have existed. If you do X, I’ll do Y. In the past, we’d make the agreement official by signing some papers in a solicitor’s office. However, with a smart contract running on a blockchain we take a different approach: first, we set out all the conditions that have to be met before the contract can be entered into; then, instead of asking a solicitor to decide when these conditions have been met, we write the whole thing in computer code and let technology act as the referee. The terms of the agreement are implemented without fuss and in a way that’s difficult to undo. If I suddenly get cold feet about some commitment I may have made, I can’t wriggle free of my obligations by finding loopholes and stirring up trouble. That’s the first interesting thing about a typical smart contract: terms and conditions are fairly hard wired.

The second interesting thing about blockchain contracts is the way details of the agreement are stored. Once the computer confirms that all the conditions have been met, the record isn’t just dumped onto one big central server which would be an obvious target for hackers. Instead, a copy of the entire record is kept on many different computers (nodes) spread out around the world. Each copy is kept in a series of linked “blocks” and each block contains a sort of digital fingerprint of all the verified information on which it is based. If someone tries to change even the tiniest detail in one block, the fingerprints won’t match and the change will be rejected. For extra security, large files (a good example for our purposes would be contract drawings) can be stored separately using a system like IPFS. The main block can be primed to keep an eye on these files to make sure that important material hasn’t been tampered with.

It didn’t take long for the earliest blockchain experimenters to see how this new technology could work as a form of money. Money, after all, is just another type of agreement. And so, around 2009, the terms "Bitcoin" and crypto entered the public imagination. Almost immediately, Bitcoin became synonymous with dodgy financial dealings and the internet was soon full of stories about international criminal gangs getting around banking regulations by paying each other in this new invisible currency.

But if we ignore all the hyperbole and look again at what an Ethereum-type blockchain involves – a system that has the same secure, tamper-proof data blocks as Bitcoin but also supports smart contracts – you can see how it might be used for things far beyond dodgy money. Anything that needs a secure, verifiable agreement could benefit from a blockchain approach, including many of the processes that underpin building and construction.

One of the more interesting examples so far of the use of blockchain in the broader construction/real estate space has been in property transactions and land registration. Anyone who’s ever bought a house, no matter where, will know that the process is slow, bureaucratic, paper-heavy and prone to error. Blockchain offers a secure, transparent alternative. In recent years Georgia (the country, not the US state), Dubai, Sweden and other jurisdictions have been testing out blockchain systems to record transfer of title. Media reports suggest the trials have been generally successful with transactions being completed sometimes in a matter of minutes.

In construction, the potential is just as easy to imagine. Take the example of a contractor completing the installation of a complicated foundation on a new project. Instead of waiting weeks for manual inspections to take place, on-site sensors confirm in real time that the work meets the agreed technical specification. That verification is automatically logged on a blockchain, which triggers immediate payment. Large companies like Skanska and Bechtel have been experimenting with these and similar approaches for quite some time, tracking materials from their source to their final installation as well as checking authenticity and compliance.

Another interesting area for potential blockchain crossover is the use of BIM. In a big public building project the architect, engineers and contractors might each start out working on the same 3D BIM model. But as the job progresses, each consultant makes one tweak here and another one there and soon various "official" versions of the same model have come into existence. When a dispute eventually erupts over whether a particular detail was formally approved, no one can be sure whose version of the detail is the “real” one.

With a blockchain-based approach, each approved version of the BIM model could be time-stamped and stored in a tamper-proof way so that a clear, verifiable record of what was agreed can be referred to. We could take this concept one step further and link the approved building model to a city’s digital twin – say, Dublin or Cork – with the building’s latest data slotted straight into the digital city model. This would mean that planners, utility providers and emergency services would have a reliable, up-to-date digital version of the building to work from. And, in fact, this is something that is already being explored in Dublin where the City Council’s partnership with DCU on creating a digital twin has received favourable coverage in the trade press.

While there has been progress in these and other areas, particularly in the private/commercial sphere, wide-scale adoption of blockchain technology in the worldwide construction industry faces a number of hurdles. For a start, regulations vary widely from region to region, making international coordination difficult. Added to that, the technology’s reputation still suffers from its early association with international criminal activity and, more recently, its environmental credentials have also been called into question. Similar to the technology involved in AI, conventional blockchain technology depends on large, power-hungry infrastructure which raises legitimate concerns about energy use and environmental impact, although it must be noted that more recent developments in the field have significantly reduced the amount of electricity to power an Ethereum-type chain.

In Ireland, there’s the added challenge of slow adoption in the public sector. The Government’s recently revised National Development Plan makes passing reference to AI, but none to blockchain. And while some of the important crypto exchanges like Coinbase and Kraken have an established presence in Dublin, there isn’t a sense that blockchain technology has made an impression on the national psyche just yet. Without a clear strategy at government level, we risk falling behind countries already using the technology to speed up land transactions and improve on the construction workflow. How a more streamlined AI/blockchain approach could improve the delivery of, for example, much needed public housing is an interesting point to consider.

This doesn’t mean we should simply bemoan our misfortune and sit around waiting for the next tech opportunity to come our way. One of the more interesting things about the rise of AI, taken in its broadest sense, is its ability to tackle problems that feel too big or too unwieldy for heavy bureaucracies to sort out. So there’s no reason we couldn’t use AI to help us work through the practical and policy challenges of bringing blockchain into our construction and property systems. If we could get the two technologies working together – AI to design streamlined processes, blockchain to guarantee their integrity – the results could be extremely positive for everyone involved. And the countries that manage to combine AI and blockchain in this way will almost certainly enjoy some real advantages. There’s still an opporutnity for Ireland to put itself out in front – but time is running out.

Blockchain can offer a secure, transparent way to record agreements, and therefore holds potential across construction and property sectors, enabling real-time verification, automating payments, and improving data reliability. Yet its adoption in this context remains limited. In this article, Garry Miley discusses the possible impacts and limitations to the technology’s implementation.

Read

Open House Europe has chosen Future Heritage as its theme for this year.[i] This reframing of “heritage” urges us to consider not only what we have inherited from past generations, but what we would like to pass down to future generations. We are custodians of what we have inherited but we cannot preserve our cities to the point of stagnation. While building for the present, we must also negotiate a relationship to the past and to the future.

In considering the importance of the past and the future in the built environment, it is helpful to first consider the nature of the human relationship to time. This was explored by the philosopher Augustine of Hippo (354–430). In his reflections on the nature of time, Augustine speculates that where the past and the future actually exist is in the mind. The past and the future are present in the mind through memory and expectation, respectively. Augustine refers to this as the distention of the mind.[ii] In the human experience of time, then, the mind is always stretched towards the past through memory, and towards the future through expectation.

In this account, the past only exists through memory. However, memory also extends beyond our minds through the act of inscription. Inscription is described by the philosopher Paul Ricoeur as “external marks adopted as a basis and intermediary for the work of memory”.[iii] These “external marks” are what make up our written and visual histories and cultural narratives; crucially, they also make up our built environment. Our cities act as an intermediary for the work of memory. This is captured by Italo Calvino in his book Invisible Cities:

The city, however, does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, the bannisters of the steps, the antennae of the lightning rods, the poles of the flags, every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls.[iv]

Layers of past inhabiting are inscribed in the buildings, streets, and squares of our cities. In our built heritage, we encounter the values and cultural narratives that previously guided the building of our cities. We reinterpret these through the lens of current sociocultural values in a perpetual renegotiation with the past. This is the work of memory.

The relationship to the past, cultivated through this work of memory, is an important aspect of the collective identity of any community. This is the case whether the place is one we have inhabited all our lives or is one that is inscribed with an unfamiliar past. For this reason, built heritage has a powerful role in the sense of identity of the inhabitants of the city. Its loss through war, natural disaster, decay, or development is often met with grief and even outrage.

In this regard, developing a city is a question of considering what memories we consider worth preserving and what future memories we would like to inscribe. The tricky balance of negotiating the relationship between the past and the future in a city can be seen in two late twentieth-century transport-infrastructure-led development projects: one in Amsterdam and one in Dublin.

In the 1970s, the city of Amsterdam’s development plan included the demolition of a large part of the central historic neighbourhood of Nieuwmarkt to make way for the city’s metro. The project proposed to replace the demolished buildings with New-York-style skyscrapers. At around the same time, the Irish transport authority planned to demolish much of the Temple Bar area in Dublin to develop a central bus station and underground rail tunnel. The historic neighbourhoods proposed for the sites of these projects were both in decline and in need of regeneration. The city authorities saw the opportunity this provided for introducing transport infrastructure for the future. A key difference in the circumstances of these projects was that Amsterdam’s had project funding readily available from government and commercial backers; Dublin’s did not.

In Amsterdam, many Nieuwmarkt buildings that had been cleared of their residents in preparation for demolition were occupied by artists and conservationists in an effort to preserve them. However, this local opposition to the demolition did not prevent it from going ahead. Instead, it culminated in some of the city’s worst ever riots, with violent clashes between those who had taken up residence in the district and the police and army sent to forcibly remove them.

Like Nieuwmarkt, Dublin’s Temple Bar area was in need of regeneration as a result of years of decline. However, in this case, funding delays led to the state transport authority letting out the properties it had acquired and earmarked for demolition. The cheap short-term rents attracted artists and small businesses. This brought new life to the area and revealed its potential as a cultural quarter. With intensifying local resistance to the plan and a new civic consciousness of the area’s potential, plans for the bus station were abandoned.

In Dublin, as in Amsterdam, there was a dissonance between the values of those altering the city and the values of those inhabiting the city. However, the delays to the Dublin project sowed the seeds of an alternative approach to the area’s development. Eventually, as part of Dublin’s tenure as European City of Culture in 1991, a competition for the rehabilitative Temple Bar Framework Plan was launched. This was won by Group 91[v] with their plan that proposed preserving much of the existing network of streets, with a handful of interventions including squares, streets, and a few key buildings.

Similarly, in Nieuwmarkt, even though a large number of buildings were demolished and the metro was built, plans for a motorway and tall office buildings were abandoned and Nieuwmarkt was ultimately rebuilt on its original street layout. This is notable as memory is not only inscribed in the materiality of the city, but also in its layout and design. In his book The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard points out that “over and beyond our memories [our formative space] is physically inscribed in us. It is a group of organic habits”.[vi] Memory is inscribed in our cities, and the space of our cities is in turn inscribed in us through choreographing our habits of use.[vii]

Learning from past instances is valuable in deciding how to develop our future heritage and recognising what values are driving our decisions. It is evident from the above examples that changes to a city should be approached with care and follow the “principles of cooperation, equity, and democracy”[viii] that underpin much of Europe’s recent history. A good guiding principle to making interventions in the city that create inclusive socially responsible future heritage is perhaps the generosity of spirit invoked by Grafton Architects' concept of “freespace”.[ix] This includes generosity to current inhabitants through collaboration and the promotion of agency and belonging, and generosity to future inhabitants, particularly by taking measures to mitigate climate change and to make our cities inhabitable in the future.

Like the mind in Augustine’s account of time, the city is stretched towards both the past and the future. Our own values determine how we approach our relationship to the past and what we desire for current and future inhabitants. Where the future exists as expectation in the mind, it exists as possibility in the built environment. The past is present in the built heritage of a site and the future is present in the possibilities that the site presents. In deciding how to alter our urban spaces we are renegotiating our relationship to our past and drawing out the city we want future generations to inherit.

In this article, Dr Sally J. Faulder, referencing this year's Open House Europe theme of "Future Heritage", considers how we ascribe value to our inherited and inhabited built fabric, and to the built heritage we seek to pass on.

Read

OUTSIDE: IN, which ran from 29 May to 20 June, was a display of the work from the UCD School of Architecture Planning and Environmental Planning. This year, the summer exhibition wanted to invite the public into our studio spaces at Richview, continuing an important conversation between architectural education and the wider professional community, sparked by the Building Change project and highlighted at the RDS Architecture and Building Expo last October. The exhibition aimed to invite the outside into our world of Richview architecture and exhibit how the next generation of UCD architects are being prepared to shape the built environment.

The exhibition draws on the ideals of the new Building Change curriculum that has been introduced into the B.Arch over the past three years, and aims to comment on the environmental, social, and economic challenges and opportunities arising in current architectural discourse. OUTSIDE:IN sought to bridge the gap between academia, industry, practice, and policy. It represented a space where the values of architectural education intersect with the realities of contemporary practice.

Featuring the work of seventy-five Master of Architecture students, the work was curated around four forward-looking Design-Research Studios, each tackling real-world challenges through the lens of climate action:

• Housing & the City – rethinking urban living and community development.

• Material Embodiment & Resources – exploring sustainable materials, construction, and structure.

• Landscape Economy & Town – investigating settlement and production through social and economic perspectives.

• Past, Future & Reuse – advancing circularity and adaptive reuse in architecture.

As well as a celebration of the students work, the opening evening began with an insightful panel discussion with panellists Ana Betancour (Urban + Architecture Agency), Lucy Jones (Antipas Jones Architects), Sarah Jane Pisciotti (Sisk Group), Emmett Scanlon (Irish Architecture Foundation) and Conor Sreenan (State Architect, Office of Public Works). The panellists were carefully selected to reflect the diverse paths which are open to us as we leave the four walls of our institution. Although panellists share a common foundation in education and practice, each has pursued different and inspiring trajectories across the architectural realm.

The panel discussion allowed us to consider and reflect on our five years of education and growth, within and outside of the studios in Richview. The overall message was of encouragement, to have confidence, be brave, be unforgiving, unrealistic, and open-minded. The variation in the panellists showed the diverse and varied opportunities and interests that can stem from an architectural education. Our education is about the fundamental ability to evaluate things, understanding our own morals, social values, interests and to ask what can architecture be? Lucy Jones described architecture as a connective tissue that sits between art, policy, developers, education, the city, and people. The field mitigates between the pragmatism of society and the desire to evoke creativity and feeling within the urban environment. As Sarah Jane Piscotti said it is “a desire to know how others think and understand their perspective”. Having seen the process from within, we know there is so much more thought, passion, values, morals, and ideas in a project that can ever be represented on two grey boards. In Richview, we create a culture of curiosity and aim to understand others and we hope to bring this forward in whatever form it may manifest.

OUTSIDE:IN has allowed Richview to open its doors and studios to friends, family and the general public. Emmet Scanlon spoke about a need to de-silo architecture and its educational institutions, making it more accessible to people not within the field. There were certainly moments throughout our education where this sort of ‘wall’ was obvious to us. There was a continuous use of inaccessible language to communicate something that may have seemed relatively simple. At times it felt as if the words were being used to throw us off intentionally. But looking back these moments also taught us to question how and why we communicate our designs in a certain way and, in particular, who we are communicating it to. Despite the challenges and hurdles, our education pushed us to critically think, to find clarity among complex situations, and to constantly strive for inclusivity within our work. It’s a reminder that architecture is not just about what’s built, but about the people, language, and connections we are creating. As we move forward, we now have the opportunity to carry these lessons with us, to make the field more transparent and approachable and to always design with intention and accessibility at the centre.

The Building Change initiative aims to bring climate literacy and sustainability into practice through developing the undergraduate curriculum. A three-year project across all architectural schools in Ireland, it encourages students to engage with and consider the climate emergency, and their impact and responsibility as architects in relation to this. To celebrate the end of the three-year programme in UCD, the Building Change Student Curators held a competition titled, ‘Making Visible the invisible’. The aim of the competition was to submit a piece of work that communicates the often unseen factors that inform design. We cannot always see air, sound, force, energy, waste, biodiversity, environmental impacts etc., yet being able to understand and visualise these systems is a vital part of architectural practice. Similarly, Building Change was often an unseen system, changing and informing education in Richview over the past three years. To celebrate this and bring light to all the innovative and positive impacts the initiative had, a collaged mural was erected in the front foyer representing Building Change’s timeline within the school, plotted in relation to wider environmental changes on a global scale. The timeline is a visual representation indicating how our education is adapting and responding to the climate emergency.

OUTSIDE: IN opened Richview’s studio doors to the public, showcasing how UCD’s architecture students are responding to today’s environmental, social, and economic challenges. This article explores how the exhibition, grounded in the Building Change initiative, reflects a shift in architectural education connecting academia, industry, and community through design, dialogue, and climate action.

ReadWebsite by Good as Gold.