It is a strange time. Conflict is general, but there is one area of surprising consensus: Una Mullally and Michael McDowell are writing columns that agree with each other [1]. The cause of this congruence between left and right is the proposed reworking of the St Stephen’s Green shopping centre – a design both correspondents decry for its blandness and generic expression [2]. In the absence of full-time built environment critics in the Irish popular press, Mullaly and McDowell have each written extensively, with different emphases, about matters of architecture, urban form, and planning. Their critiques of the proposed development express views common in our society. While James Toomey Architects’ shopping centre might not be the most important building, with its clip on "Mississippi river boat façade" [3], the journalists’ point stands: so many facades, reworkings, and new builds betray a lack of consideration of threshold, of contribution to public space, of the linking to and protection of communities, or of seeking to create humane and delightful places to live. This is not a critique of architects per se, but of our planning system.

It is worth briefly setting out the status quo: most buildings are constructed by private individuals or companies, each acting in its own self-interest. These individuated projects become the public faces of our cities and towns, shaping our movement patterns, our ability to find repose or respite, and the network of social encounters that constitute a society. Acting to regulate and temper these disparate development processes is our planning system. ‘Forward planning’ teams within local authorities shape policies in the short, medium, and longer terms, while ‘development management’ departments consider specific applications for development permission. Beyond this, An Bord Pleanála adjudicates on appeals to planning decisions throughout the state.

There is something quaint about this, a simple system for a simpler age. It assumes an episodic pace of development – where extant works can be reasoned against proposed, at a pace which allows things to cohere. It’s a system ill-equipped to respond to the contemporary pace of development. While pre-planning systems exist, feedback tends to be high-level, strategic. Points raised may often be set aside by the applicant in the aspiration that a higher body may overrule local planners. Tactics shape decisions. Sometimes a flat refusal is not in the public interest; conditions requiring the omission of a floor, or even an entire block, are reasonably common. But these retroactive measures are probably the least useful ways to ‘manage’ development.

Applicants, for their part, assemble ever more complex design teams with specialisms added as tools to bolster a case, not necessarily to improve design. Many anticipate An Bord Pleanála as the final adjudicator. There is little incentive to justify the increased time (and therefore fee) an architect or landscape designer requires for a more thoughtful approach, as this will rarely have demonstrable impact on the planning decision or the financial modelling of the proposal. None of this is the planners’ fault, but a product of the system. As we consider a major overhaul of planning regulation here [4], it is curious that there is not more debate about this aspect. The primary effect of the proposed planning reform will be a more robust and streamlined system, but not one necessarily delivering better design.

It is time to consider using design review panels. These exist in many forms in various parts of the world. Some, such as those common within universities or major corporations, are specific to institutions, or to special planning areas, while in countries such as the UK these panels form part of the general infrastructure of the planning system. Design review panels bring together diverse specialisms to critique designs as they develop. A panel may include architects, landscape architects, housing experts, community engagement experts, and many more as required. These experts, paid for their time, review applications at early and late stages and provide non-binding feedback. Review events may resemble a design review in university, with a verbal presentation and conversational feedback.

The best design review processes are timely, occurring at an early design stage. They are proportionate, recognising that not every project warrants the process: perhaps key sites, streets or scales of work are identified as triggering a review. They involve rotating panels of diverse and skilled experts, offering objective feedback in a transparent and accessible manner. Most importantly, they are advisory: they do not act to design, but to inform a design process. However, their impact can be profound, allowing decisions taken early on to greatly improve anything from a proposal’s integration within an area, to the nature of housing layouts, and even aesthetic expression. Planners naturally draw on the transcripts of these sessions – and developers, knowing this, seek to bolster the design strength of their proposal. Conversations led by design review panels can, say, make a case for increased density coupled with clear qualitative improvements. In other cases, panels may act as powerful advocates against demolition, or champion the adjustment of early ideas to cater for the full breath of diverse needs that exist within our communities.

Design review can be malleable, recruiting and developing expertise across local authority boundaries and making space for arguments which may greatly improve the built environment over time. They also make explicit to applicants a requirement for skilled, adequately resourced designers. This impact ripples beyond the specific sites being reviewed and modifies the entire development eco-system over time. Substantial literature exists internationally on the benefits of the system [5], literature which will be vital in designing a successful Irish approach. Trials are key, to allow the new system to adjust and develop in light of how it is working.

None of the above is a panacea, but it might be a way to begin responding to the valid critiques raised by commentators left and right. Design review panels have the potential to positively reshape our cities and towns, setting out a new vision of our country for decades to come.

One Good Idea is supported by the Arts Council through the Arts Grant Funding Award 2024

1. U. Mullally, "St Stephen’s Green: People will wonder why something unique was torn down for something generic", The Irish Times, 15 January 2024.

2. M. McDowell,"The sad truth is that we do not have urban planning anywhere in Ireland", The Irish Times, 20 January 2024.

3. C. Casey, Dublin: the City within the Grand and Royal Canals and the Circular Road with the Phoenix Park. New Haven, Conn., Yale University Press, 2005.

4. Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, ‘Guide to the Planning and Development Bill 2023’, www.gov.ie, 2023, available at: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/8bdf0-guide-to-the-planning-and-development-bill-2023, (accessed 05 January 2023) .

5. For example, K. Volz and S. Holden, "Case studies: Design review panels in action", Architecture Australia, Mar/Apr 2023, pp. 60-63.

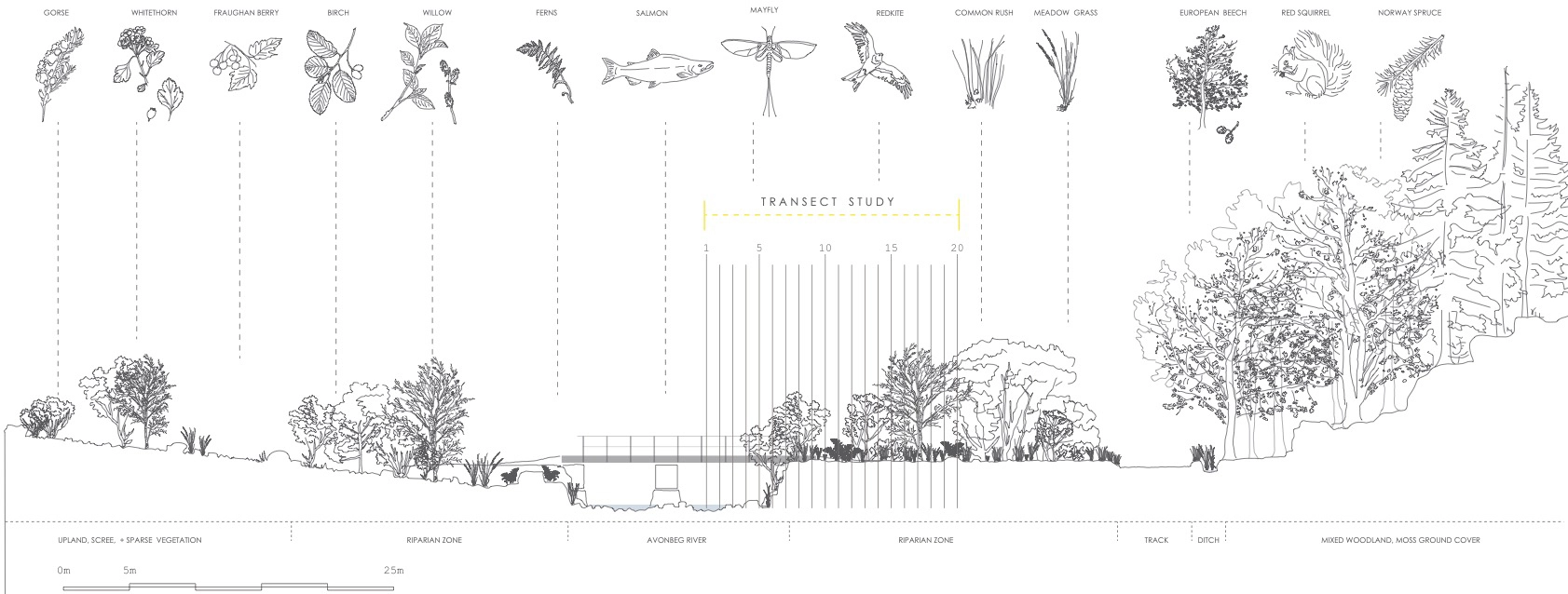

If a river could speak, what would it say? What if rivers, streams, and other waterbodies were recognised not as inanimate resources, but as living entities with their own agency? Such recognition would require a profound shift in how we regard, design, and inhabit landscapes shaped by water.

Across Ireland, rivers have shaped our cities, towns, and rural areas. They are woven into cultural identity, sustaining industrial, agricultural, and civic life. Early communities lived by the logic of water – organising around its seasonal rhythms for trade, farming, and gathering. This reciprocal relationship enabled social and economic stability. Over time, however, industrialisation and urban expansion reoriented human life away from water. Rivers were channelled into systems of economy, energy, and urban growth. As Sir William Wilde observed in his appraisal of the River Boyne and Blackwater, ‘the inhabitants of Navan, like those of most Irish towns through which a river runs, have turned their backs upon the stream’ [1]. This disconnection remains embedded in cultural perception and physical planning.

Today, climate volatility and ecological degradation demand a re-examination of our societal relationship to water. Riverscapes are increasingly fragile; their loss would severely undermine biodiversity and ecosystem resilience. The contemporary challenge lies in rediscovering the ecological intelligence that rivers possess and reinstating modes of coexistence that value water as a living system [2].

Rivers are dynamic environments shaped by erosion, flooding, and time – forces that, when left undisturbed, sustain balance. But industrial pollution, agricultural intensification, and mismanaged urban runoff have disrupted these processes. Such practices have wounded river ecologies and diminished their capacity for self-regulation. Nevertheless, as Robert MacFarlane’s explorations in his book Is a River Alive demonstrate, ‘hope is the thing with rivers’ [3]. Given space and care, river systems can recover rapidly. This possibility underscores the importance of stewardship over exploitation. Restoration begins with recognising the river as a partner in regeneration rather than a passive resource.

Rebalancing human–river relations requires the integration of ecological science, cultural practice, and participatory engagement. A regenerative and reciprocal approach would prioritise both ecological function and social value. Artistic practice can serve as a mediating tool, helping communities to perceive and interpret the agency of water. The act of ‘deep listening’ – through soundscape studies and field recordings – offers a method of reconnecting with river environments and can re-sensitise us to the voices of the non-human world.

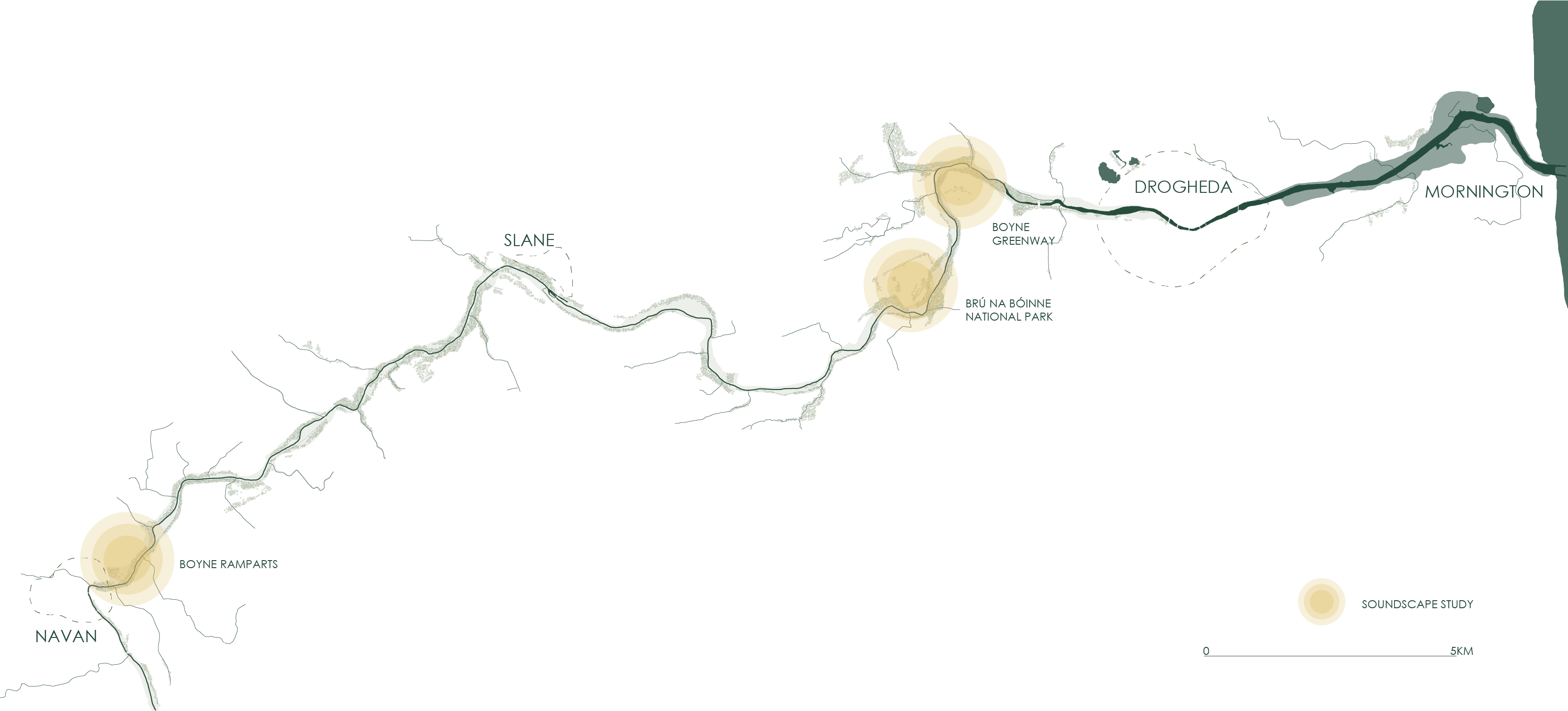

Sound is an indicator of ecological vitality. The sonic landscape of a healthy river – birds, insects, flowing water, and wind – reflects biodiversity. There is as much to learn from silence as from sound. Using extended field recording tools such as hydrophones, contact microphones, and acoustic sensors, we can listen beneath the surface, to trees, soil, and water itself. Ecologists increasingly employ soundscape spectrogram analysis to assess habitat quality and species distribution. Publicly accessible app identifiers, such as Merlin or Biodiversity Data Capture, enable citizens to participate in environmental monitoring through listening. Thus, sound becomes both a scientific and a democratic mode of attention. These slow-observation techniques help us grasp both the strength and vulnerability of these ecosystems, enabling us to take the right actions in the right places to support the river [4].

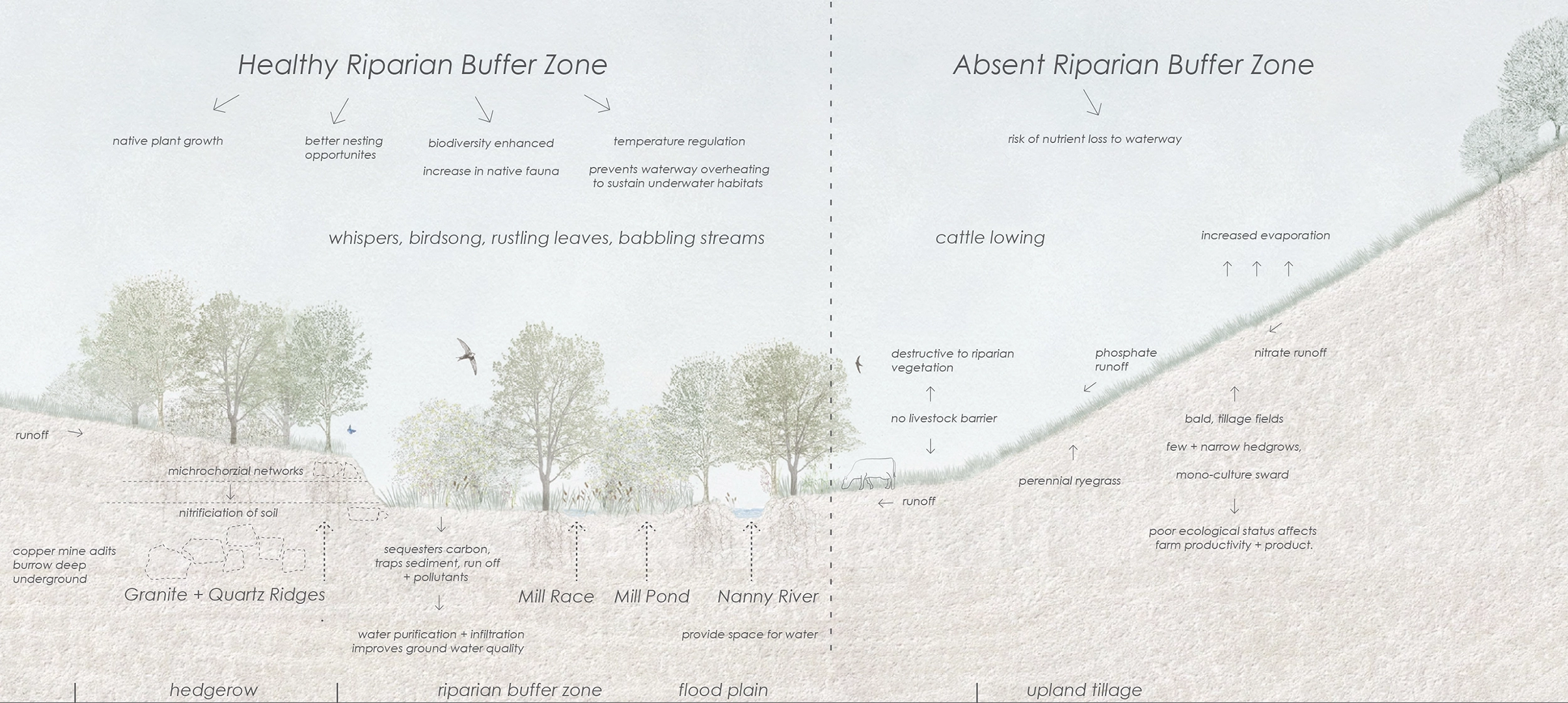

The ecological health of rivers is intrinsically linked to riparian buffer zones: the vegetated margins between land and water. These areas function as natural biofilters, trapping sedimentation, absorbing pollutants, and stabilising banks while providing shelter, habitat, and food for countless species. Despite their importance, many have been drained or grazed to maximise land use. Nutrient loss, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus runoff, contributes to eutrophication, whereby water becomes overly enriched, leading to a dense growth of algae and aquatic plants. These blooms reduce oxygen levels, and oxygen is required to support fish and other aquatic life [5]. Controversially, the EU Nitrates Directive has permitted Ireland to continue to exceed the standard manure limit of 170 kg nitrogen per hectare, albeit with stricter requirements to protect water quality [6].

In the Boyne Valley catchment, where agriculture is the main significant pressure, only one river is achieving high ecological status and 51% of waterbodies are at risk of not meeting their environmental objectives [7]. The River Boyne is a designated SAC and SPC, however, riparian habitats are fragmented, degraded, or absent with few native woodlands remaining. Inland Fisheries Ireland have warned that Atlantic salmon stocks have fallen to some of the lowest levels on record and important river birds such as the lapwing and sand martin are ‘of conservation concern’ [8]. The decline of these species indicates a broader threat to the entire river system. In addition, the Department of Housing has proposed to classify certain stretches of the Boyne and Blackwater as ‘heavily modified water bodies’, a move which could essentially relegate our legal obligations to restore them [9].

The restoration of riparian buffers is central to water quality improvement and climate adaptation. Properly managed buffers are essential for intercepting and reducing diffuse pollution before it reaches waterbodies [10]. Beyond their ecological function as green corridors, riparian buffers also support human wellbeing, offering spaces for play, recreation, education, and multi-sensory restoration. Walking along a river, listening to it, and observing its cycles of change can help regulate emotions, reduce stress, and elevate mood. Three recent EPA research programme studies (2014–2022) – GPI Health, NEAR Health, and EcoHealth – found measurable physical, mental, and social health benefits associated with access to green and blue spaces[11]. In urban contexts, these buffers can reconnect communities with waterways that have long been inaccessible or overlooked. Such holistic relationships with nature can foster healthier communities and help futureproof society against environmental uncertainty.

Rezoning riparian land as cultural and ecological corridors offers a framework for integrating environmental resilience with public amenity. Public parks, heritage landscapes, and post-industrial sites can host new programmes that coexist with water while balancing protection, access, and conservation. Instead of resisting flooding through hard engineering, adaptive design can accommodate seasonal pressures through wetlands, soft embankments, and absorbent landscapes.

The River Boyne provides a valuable case study. Along its course, several significant public sites – Oldbridge, Newgrange, Slane, Trim Castle, and Brú na Bóinne [12] – offer opportunities to lead this change. These areas, already rich in heritage and ecological value, could restore riparian zones and improve biodiversity while enhancing public space for human and non-human amenity. Similarly, the proposed Boyne Greenway between Navan and the Bridge of Peace could become a model of designing with the river as a living stakeholder rather than as an element of infrastructure.

Building solutions from the ground up is vital. Local industries, landowners, and government bodies are accustomed to the old extractive land use practices. Schemes such as IRD Duhallow’s LIFE project [13] or the Inishowen Rivers Trust’s ‘Cribz’ [14] managed to bring relevant stakeholders together to highlight their role in their local river's conservation. Both projects found that community-based engagement promoted environmental stewardship and action in their localities. Artistic and cultural interventions can complement scientific approaches by cultivating empathy and imagination. Place-based workshops that integrate art, ecology, and citizen science invite participants to engage with rivers experientially, through listening, recording, and collective observation [15]. Such participatory methods expand environmental knowledge beyond data collection to include sensory, emotional, and ethical dimensions. They encourage us to slowdown, listen, and experience the river directly. These activities foster empathy and understanding, reconnecting participants with the landscape.

Creativity can help us reimagine our systems for climate adaptation. Partnerships between artists, scientists, local authorities, and environmental groups can strengthen collective capacity for change. Local arts organisations provide platforms for dialogue and dissemination, helping to transform awareness into action. Interdisciplinary collaboration bridges the gap between ecological science and public perception, and can generate community-driven models of stewardship.

Led by Scape Architects, the Chattahoochee RiverLands Greenway Study in Atlanta, Georgia, proposes a linear network of greenways, blueways, and parks, shaped through local interviews, immersive experiences, participatory design charrettes, and public forums [16]. Following a similar approach, Take Me To the River – a collaborative initiative between the Solstice Arts Centre and Cineál Research & Design – has been cultivating connections with the local council, water authorities, river-trust networks, and communities. Through creative, site-based public workshops and exploratory mapping exercises, the project is developing a layered understanding of the river catchments of County Meath [17].

Ireland’s Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss has called for the recognition of rights of nature in the Constitution, to provide a stronger legal framework as we face accelerating species decline and biodiversity loss [18]. Assigning the concept of ‘riverhood’ to waterways acknowledges their intrinsic right to exist, flow, and regenerate, independently of human interests.

Reimagining rivers as sentient entities invites both ethical and practical transformation. It challenges dominant paradigms of extraction and human control and instead proposes relationships grounded in indigenous and ecological understandings of reciprocity. In Celtic mythology, the goddess Bóinn’s spirit became the River Boyne, giving it associations with poetry, fertility, and wisdom.

Restoring riparian buffers and ecological corridors can enable rivers to function as autonomous living systems within interconnected landscapes. Healthy rivers create natural pathways for wildlife, filter our water, and stabilise our climate. With ecological renewal, interdisciplinary collaboration, and creative engagement, they canal so provide us with spaces for reflection, imagination, and belonging.

If a river could speak, it might remind us that every act of care or neglect upstream reverberates downstream and that stewardship begins with attention. To listen to rivers is to acknowledge our shared dependence within a living system.

In this article – timely, in light of recent flood events – Phoebe Brady and Sarah Doheny argue that integrating environmental resilience with public amenity and treating rivers as living stakeholders, rather than as elements of infrastructure, is essential if we are to ensure the survival of our watercourses and our ecology.

Read

Three seemingly unrelated stories caught my eye in the news in recent months. In the Dublin suburb of Dundrum, residents spoke out in opposition to a proposal to build an “aerial delivery hub” in the centre of the town.[1] A meeting organised by local politicians was attended by the chief executive of the drone company, but this wasn’t enough to convince the citizens of Dundrum that the new hub was a good idea.

A few weeks earlier, Irish billionaire businessman Dermot Desmond was reported as having described the long-awaited Metrolink project as obsolete and “a monument to history”.[2] He argued that autonomous vehicles operated by artificial intelligence would make the rail line redundant, would cut the number of vehicles on the road dramatically, and eliminate congestion. His argument was dismissed by transport experts and citizens alike.

More recently, in the annual scramble for housing, students in Galway spoke in despair about the lack of available accommodation, noting that there are currently over 1,000 properties listed on Airbnb for Galway, while there are only 111 properties to rent on Daft.ie (in fact, the figure maybe below seventy).[3]

What these three stories have in common is that they are all underpinned by technologies which aim to minimise social interaction within our cities, based not on a desire to provide a service to society (whatever their proponents might claim), but to extract maximum profit by eliminating the cost of people doing real work.

Canadian writer Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification” in 2022 to describe how online platforms switch from serving their users, to serving their business customers at the expense of their users, to finally serving only their shareholders, resulting in a poor service that both users and business customers are locked into. A similar process can be observed in the way technology is used to deliver services in our cities.

Airbnb is an undoubtedly useful platform for people looking for short-term accommodation for city breaks and holidays. When it was founded in 2008, it was celebrated as a means to connect individual travellers with homeowners who had space to spare, allowing users to bypass overpriced hotels and find affordable accommodation. On the face of it, this seems like a worthy endeavour, helping to connect people and to make more efficient use of available accommodation.

Fast forward seventeen years, and the impact of Airbnb on housing availability and on mass tourism is causing a backlash in cities across the globe. Barcelona plans to ban short-term rentals from 2028 in response to a housing crisis that has priced workers out of the market. New York City has introduced laws to restrict short-term lettings and block non-residents from letting out properties. Restrictions are also in place in Berlin, Lisbon, and Athens. Elsewhere, short-term lettings are highly regulated to limit over-tourism. Rather than connecting people, the rise of short-term letting has resulted in a sterilisation of parts of our urban centres where key-boxes proliferate and visitors never physically meet their hosts.

The plan for drone deliveries is just the next stage in a progression from takeaway restaurants doing their own deliveries, to online delivery platforms operating from dark kitchens. Again, it comes from a worthy pretext – to help restaurants connect with their customers and to make ordering takeaway food simpler for customers – but in this case, the enshittification stage results in streetscapes where restaurants no longer have a public presence, but are attended by gig-economy workers who act as intermediaries between businesses and citizens. The drone delivery concept goes one step further, replacing that human intermediary with a machine. The citizens of Dundrum certainly don’t see how that transaction is of benefit to them.

A similar progression can be seen from the redesign of our cities to suit the private motor car and the well-documented impact that has had on social interactions in the city, to the proliferation of ride-hailing apps, and now the notion that AI-powered driverless cars are the future of urban transport. Though the ride-hailing apps promised an end to congestion and reduced car ownership, the reality was very different – more congestion and more cars – and any system of AI-powered driverless cars will be governed by the same commercial imperatives to increase car miles on city roads. Again, where, in this, is the benefit to citizens?

A city is a community of citizens. At its core, it exists for the people who live there, and it thrives on social interaction. But what these technologies are doing, or proposing to do, along with things like self-service check outs, dark kitchens, and co-living units (which, despite their name, are fundamentally isolating environments), is to strip away that core. Removing human interaction in the name of efficiency and cost effectiveness is ultimately to the benefit of shareholders rather than citizens.

The Dublin city motto, “Obedientia Civium Urbis Felicitas” (Happy the city where citizens obey), has come in for some criticism recently. The Dublin InQuirer newspaper ran an unofficial poll earlier this year to choose a new, more appropriate motto for the modern city, and the winning entry changed just one word – “Participatio Civium Urbis Felicitas” (Happy the city where citizens participate).[4] That participation should be not just in the democratic functions of the city, but in the life of the city, in the culture of the city, and in the community of the city.

As we are assailed with technological solutions purporting to improve the lives of citizens, let’s consider them through the lens of the happiness of the city and its citizens. This is not a rejection of technology, but an acknowledgement that ultimately, technology should serve the citizens. If our cities are to thrive into the future, let’s recognise the importance of participation and prioritise measures that encourage social interaction and build social cohesion.

Ciarán Ferrie makes the case for more citizen participation in city life, culture, community, and democracy.

Read

Our bodies do the work, do we think of them when they are working?

Feet ache from standing, backs tire from lifting, shoulders ache from poor posture at a desk. We sit down, stand up, take a break, take refreshment. In some workplaces, there is consideration of the worker and their body: canteens are provided, bathrooms are kept clean, and the ergonomics of a desk are contemplated. All of this relies upon the acknowledgement of, the visibility of, certain types of work and workers. If we turn our attention to the city as a workplace – specifically, the streets, thresholds, parks and pavements that make up the public realm in the city and that act as a place of work for many workers – how does it accommodate the bodies of workers? Is it hospitable?

Over time, the perceived value of certain types of work, and consequently certain types of workers, has fluctuated. When seen as essential to the economy, to growth, the needs and availability of workers are considered, and their ability to advocate for better working conditions is strengthened. This has occasionally resulted in an architecture that responds directly to workers’ needs. We might take the example of pithead baths, communal bathing facilities that were built close to coal mines in the early twentieth century. Here, miners could change and bathe; the dust and dirt of the colliery becoming the responsibility of the mine itself and not the worker and their home. In Architecture and the Face of Coal: Mining and Modern Britain, by Gary Boyd, we follow the development and eventual obsolescence of this distinctive typology, pointing to the transitory nature of coal mining as one of the reasons for the short lifespan of the baths and for their fading from view in histories of modernist architecture in Britain.[i] So we have an example of an architecture that springs up in response to workers’ needs, but that also mirrors the changing status of the workers themselves.

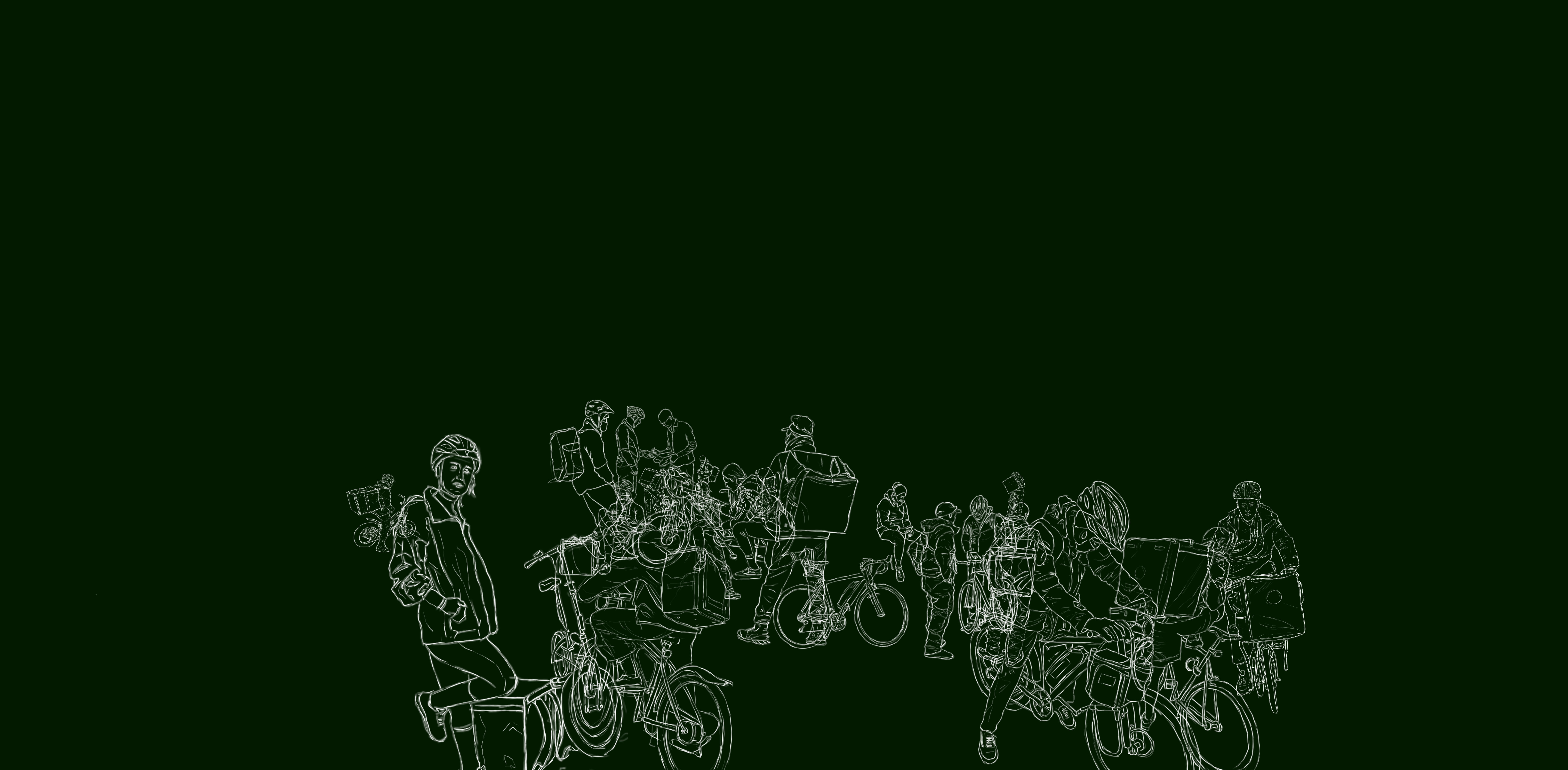

The value of different types of work is something that we continue to grapple with and that contributes to inequality locally and globally. Precarity is widespread.[ii] Nowhere is the daily reproduction of the worker more difficult and given less consideration than in the city workplace. A conspicuous example of precarious and disembodied labour is the fleet of food delivery riders that has grown in response to the evolution of online delivery platforms. This new virtual infrastructure has resulted in, but takes no responsibility for, a workforce that is reliant on the fabric of the city. While there has been recent media coverage of the riders' problematic working conditions,[iii] there has been less discussion about the pragmatic and bodily realities of their work, where they contend with weather, traffic, criminality and so on.

In The Practice of Everyday Life, historian and cultural theorist Michel de Certeau sets out a model whereby power structures are discernible by the “strategies” of agencies and institutions, representatives of the state or of commercial interests; the organising logic of city planning, for instance, or the virtual frameworks that map, track, and influence. Against, or within, these strategies are the “tactics” of the other; the citizen, the customer, or, to employ de Certeau’s preferred term, the user.[iv] If we pay close attention to the city workplace, we start to see the “strategies” and “tactics” at play, the creative and opportunistic ways of “making do” that individual riders employ in their everyday life: they rest against walls and railings; they take shelter under canopies and in ad hoc repair shops; they take shortcuts, crosscuts over rainslick tracks or in the narrowing gap between a bus and a van; they take risks;[v] they sit on park benches and at the feet of statues.

At O’Connell Monument:

Do you eat your lunch here?

“Yes, this is my office chair.”[vi]

A warehouse on Henry Place holds a rental and repair shop, renting primarily to food delivery workers. The building is a protected structure that is decaying as it awaits a contested redevelopment.[vii] A single open space is divided into two zones by a low plywood barrier: public (for rental) and private (for repair). Bikes stand ready. Metal shelves along the east wall hold the accessories that might be required by a rider. In front, a desk where forms are filled and rent is paid. In a corner, some sofas face a TV screen. A fridge, microwave and kettle provide basic facilities.

On Henry Place:

Do you take a break here?

“Yes, this is the only place that we are able to eat because we rent the bikes here, so they let us use the microwave, the refrigerator... This is the only place in the city that we can have a little space together to eat something.”

On this backland site, a temporary and informal responsiveness is demonstrated. The city user improvises on the ground, while elsewhere, a debate rages about value. In contrast to the windowsills and kerbstones that are often places of momentary rest for a delivery rider, a dilapidated and impermanent structure gives a sense of shelter and retreat, making space for camaraderie and some degree of bodily comfort.

On O’Connell Street:

Do the delivery companies provide any equipment or clothes for you?

“Not exactly, once in a while they give something for free, like the bag and the jacket, but not all the time. The jacket is more for promotion; it gets wet, you get wet anyway. We have to be careful because we can get sick most of the time, because the rain makes our bodies very cold. We have to be extra careful when it’s wet.”

Where previous communities of workers had their needs considered, as in the construction of pithead baths for miners, for example, it was possible to point to a single employer with responsibility for the welfare of their workers. Groups of workers could agitate and negotiate for facilities, for practical solutions to tangible problems. Emerging from a pit with body and clothing covered in black coal dust led to straightforward questions about washing, changing, eating dinner, and storing clothes during the working day. Improvements in conditions for miners were realised because these workers were together, situated, and visible. Another historical example of situated workers’ facilities was the series of green huts built by the Cabmen’s Shelter Fund in late-nineteenth-century London. The shelters provided hot drinks and food, a place to read the paper for cab drivers, answering a series of pragmatic, corporeal needs. Like many Victorian philanthropic efforts, they came with an undertone of self-serving paternalism. Now with a protected conservation status, a handful of shelters are still in use, the interiors remaining the exclusive preserve of cab drivers.

Today, in corporate[viii] settings, the body is considered in great detail. Ergonomic assessments are exacting in their appraisal of a body at a desk: the length of shin (footstool), the height of eye (monitor stand), the reach and range of forearm (vertical mouse). Training is provided in how and what to lift. In theory, an employer is responsible for assessing these risks to the body regardless of the location of their employee. But in an era of modern piecework, who cares for the pieceworker? And is there a parallel between the hands-offishness of employers and our attitude to city streets and passageways?

Delivery riders are visible in the city but untethered, distributed through the network of the streets, finding their own informal gathering places. They are not employees; they are independent contractors. This status allows them to be light-footed within a network of regulations and legalities.[ix] The subcontracting of accounts with various delivery companies, for instance, results in a grey market of official and unofficial riders. These tactics have their mirror in the ways in which riders improvise occupation of streets and pavements, and act, to a degree, on the city; they are limited, however, in how they might shape the city to their needs.

Emerging from a tradition that prioritises urban commerce and suburban living, we plan for the street as a thoroughfare, an artery, thinking mostly of flow, of efficiency. There is arguably a parallel prioritisation of the commuter worker within the workforce. Certain dimensions are assigned for cars and buses, for bicycles and pedestrians to move seamlessly from the city centre to the periphery. This diminishes the value of the urban realm as a place to be, to dwell. What if we were to see (or return to) the streetscape, the weather-world[x] of paths, gratings and doorways, of tarmacadam and streetlights, as a single, integrated space that hosts diverse needs and functions, including those of city workers? The sense of the city as a place to move through can be challenged by an ambition to make a hospitable city: a place of rest, shelter and conversation. Acknowledging the public realm as a workplace might prove a catalyst for an inclusive approach to city-making, considerate of all bodies and all work.

Our bodies do the work. In this article, Anna Cooke asks: do we think of them when they are working?

ReadWebsite by Good as Gold.