The COP28 climate talks in Dubai concluded one week ago at the time of writing. Astonishingly, it is the first time in COP's thirty-year existence that a 'transition away from fossil fuels' [1] has formed part of the final discussion. Experts argue, however, that despite the significance and potential ramifications of this outcome, we are still nowhere near to achieving our goal of a 43% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 [2].

In part, this problem arises from how we see value in our world. The traditional value systems which we have always adhered to create a dichotomy of what is and is not valuable. Case in point: we still value fossil fuels enough to accept the destruction that we know they cause.

We judge everything in terms of value: monetary value, historical value, cultural value, political value, and so on. And of course, value systems exist for a reason – they are the decision-making processes through which we determine where to focus energy and interest. However, the flip side of this coin is the invalidation of that which we have decided is of lesser – or no – value. The inequality inherent in these systems is evident when we consider which cultures are prioritised, whose traditions are supported, and what narratives are encouraged.

Considering value systems as they relate to architecture, that which is discarded also comes at high cost. Engaging with the built environment requires engagement with physical resources and materials. In the context of the climate emergency, how might we reassess architecture's value systems, perhaps in a way that might better equip us to address the crisis at hand?

We might first look to the existing value systems that prevail within architecture. Traditionally, we assessed built fabric for its historical significance, cultural importance, aesthetic qualities, craftsmanship, and so on. We rarely question the value of a 100-year old town hall made from local stone in the middle of a country town; and why would we? It's obvious.

In recent years, the lenses through which we measure value have diversified, from Assemble's Granby Four Streets project in Liverpool, arguing for community strength and pride as a value to be supported and strengthened through even the most everyday of housing estates, to Forensic Architecture’s studies of the built environment for its value as evidence in legal and political processes.

Or, to the value of architecture as a vessel for the accumulation of everyday collective memory, be that positive or negative. We, as part of CoLab81-7 [3], recently undertook such a study with students from the School of Architecture at UCD within the former Magdalene Laundry buildings on Sean McDermott Street, Dublin. Within the format of a month-long drawing workshop, the students were tasked with examining the constructed fabric of the remaining buildings, including any – and, importantly, all – traces of inhabitation that they observed during their visit.

To begin, students carefully surveyed a route through the convent building from public to private; from the heavy timber front door at street level, to the (almost) empty nuns’ rooms on the top floor. Along the way, the students recorded everything they witnessed: every tile, door handle, window, electrical box, light fitting and curved handrail, but also every scrap of newspaper and piece of detritus, even the long-dead pigeons littering the staircase. The study raised as many questions as answers: why, for example, the formica vanity sink with five inbuilt toothbrush holders, installed in the bedrooms of nuns expressly forbidden from ever starting a family?

The CoLab81-7 study fed into the efforts of a larger advocacy group known as Open Heart City; the name a reference to open heart surgery and its system of precise yet radical intervention. The aim of this intense and comprehensive survey was to unearth both the seen and unseen qualities and questions of the laundry‘s spaces, studying permanent and temporal traces made by both time and occupancy to examine how the building's architecture supported or facilitated its carceral past. The ambition was to identify some precise yet radical move that might bring new life to a lifeless place.

But what about the ugly 80's prefab office block on a lucrative city-centre site? Such buildings are routinely demolished due to market pressures and public disinterest; the effort, energy and material resources which went into their construction still falling on the not valuable side of our value coin.

The architecture collective Material Cultures argues that 'whenever we build, we either contribute to or counteract processes of change' [4]. If we are going to address the looming climate disaster, the greatest change humankind has ever known, then we must act in radical and unconventional ways. We must start by seeing everything as valid – the 100-year old town hall and the 80s office block, the 90s housing estates and the abandoned institutional buildings with difficult pasts. As architects, we are in a unique position to both influence and facilitate this change; to act like physicians, working to identify the most efficient, least harmful way to treat the patient without ever debating whether the patient deserves saving in the first place.

As soon as possible, the world must free itself from fossil fuels, and we must recalibrate our understanding of what is valuable and what is not. We could begin, for example, by eliminating the idea that anything is without value; instead starting with a baseline of 100% value in our existing buildings, materials and resources and working backwards from there. Like a doctor presented first with symptoms and then with scalpels, we would endeavour to spend time understanding the 'patient' in their entirety, synthesising their past history and present condition, before using the tools available with precision to ensure a healthy future and a long life.

One Good Idea is supported by the Arts Council through the Arts Grant Funding Award 2024

1. 'Unpacking COP28: Key Outcomes from the Dubai Climate Talks and What Comes Next', World Resources Institute [website], 2023, Available at: https://www.wri.org/insights/cop28-outcomes-next-steps, (accessed 20 December 2023).

2. 'New Analysis of National Climate Plans: Insufficient Progress Made, COP28 Must Set Stage for Immediate Action', United Nations Climate Change ebsite),2023, Available at: https://unfccc.int/news/new-analysis-of-national-climate-plans-insufficient-progress-made-cop28-must-set-stage-for-immediate, (accessed 20 December 2023).

3. CoLab81-7 is a collaboration between three emerging architectural practices, Denise Murray, Dún-Na-dTuar, and plattenbaustudio. In recent years the collective has expanded to include researchers, software engineers, social scientists and advocacy groups.

4. Material Cultures, Material Reform, UK, MACK, 2022, p. 16.

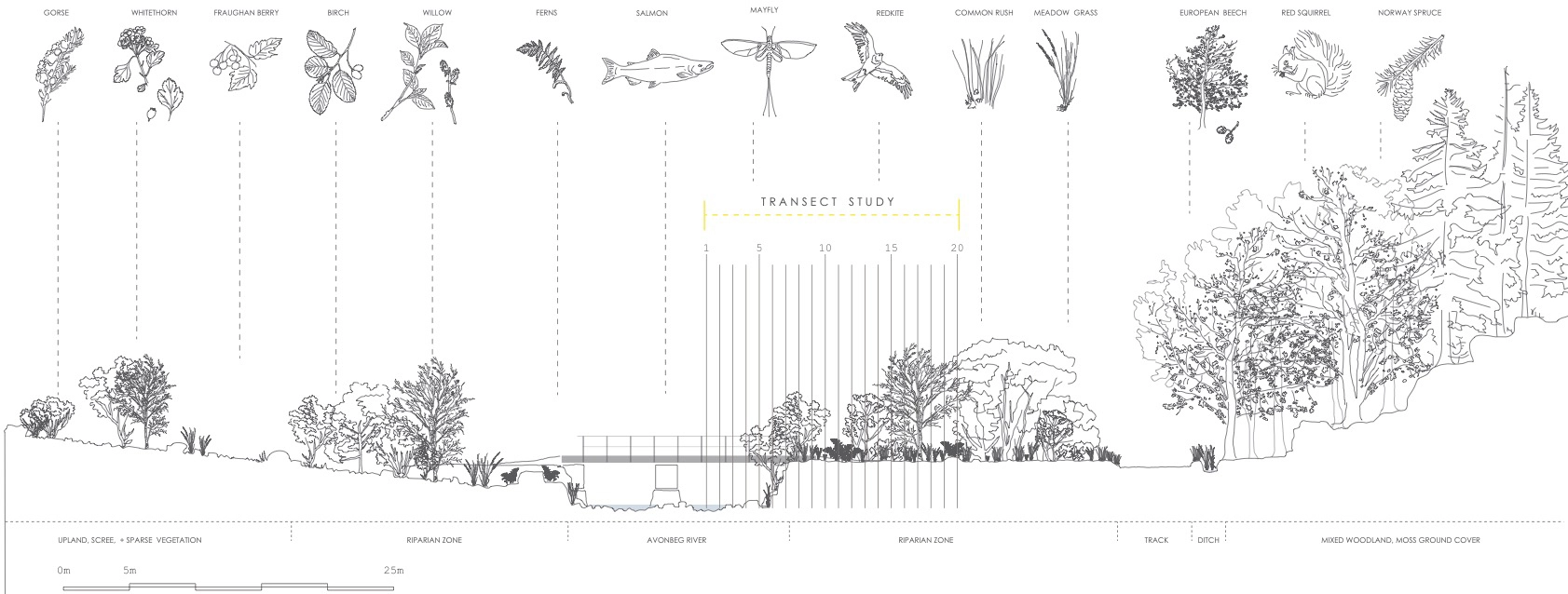

If a river could speak, what would it say? What if rivers, streams, and other waterbodies were recognised not as inanimate resources, but as living entities with their own agency? Such recognition would require a profound shift in how we regard, design, and inhabit landscapes shaped by water.

Across Ireland, rivers have shaped our cities, towns, and rural areas. They are woven into cultural identity, sustaining industrial, agricultural, and civic life. Early communities lived by the logic of water – organising around its seasonal rhythms for trade, farming, and gathering. This reciprocal relationship enabled social and economic stability. Over time, however, industrialisation and urban expansion reoriented human life away from water. Rivers were channelled into systems of economy, energy, and urban growth. As Sir William Wilde observed in his appraisal of the River Boyne and Blackwater, ‘the inhabitants of Navan, like those of most Irish towns through which a river runs, have turned their backs upon the stream’ [1]. This disconnection remains embedded in cultural perception and physical planning.

Today, climate volatility and ecological degradation demand a re-examination of our societal relationship to water. Riverscapes are increasingly fragile; their loss would severely undermine biodiversity and ecosystem resilience. The contemporary challenge lies in rediscovering the ecological intelligence that rivers possess and reinstating modes of coexistence that value water as a living system [2].

Rivers are dynamic environments shaped by erosion, flooding, and time – forces that, when left undisturbed, sustain balance. But industrial pollution, agricultural intensification, and mismanaged urban runoff have disrupted these processes. Such practices have wounded river ecologies and diminished their capacity for self-regulation. Nevertheless, as Robert MacFarlane’s explorations in his book Is a River Alive demonstrate, ‘hope is the thing with rivers’ [3]. Given space and care, river systems can recover rapidly. This possibility underscores the importance of stewardship over exploitation. Restoration begins with recognising the river as a partner in regeneration rather than a passive resource.

Rebalancing human–river relations requires the integration of ecological science, cultural practice, and participatory engagement. A regenerative and reciprocal approach would prioritise both ecological function and social value. Artistic practice can serve as a mediating tool, helping communities to perceive and interpret the agency of water. The act of ‘deep listening’ – through soundscape studies and field recordings – offers a method of reconnecting with river environments and can re-sensitise us to the voices of the non-human world.

Sound is an indicator of ecological vitality. The sonic landscape of a healthy river – birds, insects, flowing water, and wind – reflects biodiversity. There is as much to learn from silence as from sound. Using extended field recording tools such as hydrophones, contact microphones, and acoustic sensors, we can listen beneath the surface, to trees, soil, and water itself. Ecologists increasingly employ soundscape spectrogram analysis to assess habitat quality and species distribution. Publicly accessible app identifiers, such as Merlin or Biodiversity Data Capture, enable citizens to participate in environmental monitoring through listening. Thus, sound becomes both a scientific and a democratic mode of attention. These slow-observation techniques help us grasp both the strength and vulnerability of these ecosystems, enabling us to take the right actions in the right places to support the river [4].

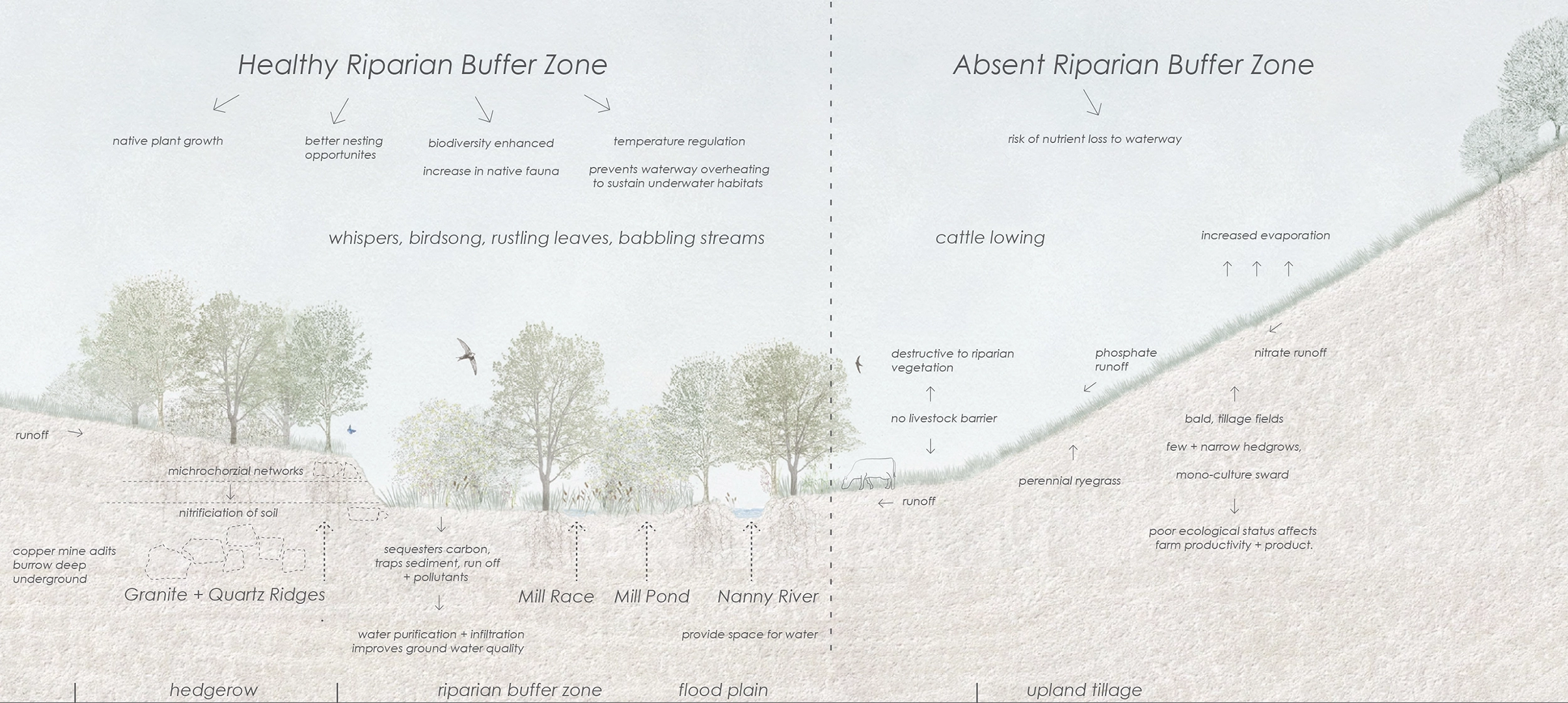

The ecological health of rivers is intrinsically linked to riparian buffer zones: the vegetated margins between land and water. These areas function as natural biofilters, trapping sedimentation, absorbing pollutants, and stabilising banks while providing shelter, habitat, and food for countless species. Despite their importance, many have been drained or grazed to maximise land use. Nutrient loss, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus runoff, contributes to eutrophication, whereby water becomes overly enriched, leading to a dense growth of algae and aquatic plants. These blooms reduce oxygen levels, and oxygen is required to support fish and other aquatic life [5]. Controversially, the EU Nitrates Directive has permitted Ireland to continue to exceed the standard manure limit of 170 kg nitrogen per hectare, albeit with stricter requirements to protect water quality [6].

In the Boyne Valley catchment, where agriculture is the main significant pressure, only one river is achieving high ecological status and 51% of waterbodies are at risk of not meeting their environmental objectives [7]. The River Boyne is a designated SAC and SPC, however, riparian habitats are fragmented, degraded, or absent with few native woodlands remaining. Inland Fisheries Ireland have warned that Atlantic salmon stocks have fallen to some of the lowest levels on record and important river birds such as the lapwing and sand martin are ‘of conservation concern’ [8]. The decline of these species indicates a broader threat to the entire river system. In addition, the Department of Housing has proposed to classify certain stretches of the Boyne and Blackwater as ‘heavily modified water bodies’, a move which could essentially relegate our legal obligations to restore them [9].

The restoration of riparian buffers is central to water quality improvement and climate adaptation. Properly managed buffers are essential for intercepting and reducing diffuse pollution before it reaches waterbodies [10]. Beyond their ecological function as green corridors, riparian buffers also support human wellbeing, offering spaces for play, recreation, education, and multi-sensory restoration. Walking along a river, listening to it, and observing its cycles of change can help regulate emotions, reduce stress, and elevate mood. Three recent EPA research programme studies (2014–2022) – GPI Health, NEAR Health, and EcoHealth – found measurable physical, mental, and social health benefits associated with access to green and blue spaces[11]. In urban contexts, these buffers can reconnect communities with waterways that have long been inaccessible or overlooked. Such holistic relationships with nature can foster healthier communities and help futureproof society against environmental uncertainty.

Rezoning riparian land as cultural and ecological corridors offers a framework for integrating environmental resilience with public amenity. Public parks, heritage landscapes, and post-industrial sites can host new programmes that coexist with water while balancing protection, access, and conservation. Instead of resisting flooding through hard engineering, adaptive design can accommodate seasonal pressures through wetlands, soft embankments, and absorbent landscapes.

The River Boyne provides a valuable case study. Along its course, several significant public sites – Oldbridge, Newgrange, Slane, Trim Castle, and Brú na Bóinne [12] – offer opportunities to lead this change. These areas, already rich in heritage and ecological value, could restore riparian zones and improve biodiversity while enhancing public space for human and non-human amenity. Similarly, the proposed Boyne Greenway between Navan and the Bridge of Peace could become a model of designing with the river as a living stakeholder rather than as an element of infrastructure.

Building solutions from the ground up is vital. Local industries, landowners, and government bodies are accustomed to the old extractive land use practices. Schemes such as IRD Duhallow’s LIFE project [13] or the Inishowen Rivers Trust’s ‘Cribz’ [14] managed to bring relevant stakeholders together to highlight their role in their local river's conservation. Both projects found that community-based engagement promoted environmental stewardship and action in their localities. Artistic and cultural interventions can complement scientific approaches by cultivating empathy and imagination. Place-based workshops that integrate art, ecology, and citizen science invite participants to engage with rivers experientially, through listening, recording, and collective observation [15]. Such participatory methods expand environmental knowledge beyond data collection to include sensory, emotional, and ethical dimensions. They encourage us to slowdown, listen, and experience the river directly. These activities foster empathy and understanding, reconnecting participants with the landscape.

Creativity can help us reimagine our systems for climate adaptation. Partnerships between artists, scientists, local authorities, and environmental groups can strengthen collective capacity for change. Local arts organisations provide platforms for dialogue and dissemination, helping to transform awareness into action. Interdisciplinary collaboration bridges the gap between ecological science and public perception, and can generate community-driven models of stewardship.

Led by Scape Architects, the Chattahoochee RiverLands Greenway Study in Atlanta, Georgia, proposes a linear network of greenways, blueways, and parks, shaped through local interviews, immersive experiences, participatory design charrettes, and public forums [16]. Following a similar approach, Take Me To the River – a collaborative initiative between the Solstice Arts Centre and Cineál Research & Design – has been cultivating connections with the local council, water authorities, river-trust networks, and communities. Through creative, site-based public workshops and exploratory mapping exercises, the project is developing a layered understanding of the river catchments of County Meath [17].

Ireland’s Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss has called for the recognition of rights of nature in the Constitution, to provide a stronger legal framework as we face accelerating species decline and biodiversity loss [18]. Assigning the concept of ‘riverhood’ to waterways acknowledges their intrinsic right to exist, flow, and regenerate, independently of human interests.

Reimagining rivers as sentient entities invites both ethical and practical transformation. It challenges dominant paradigms of extraction and human control and instead proposes relationships grounded in indigenous and ecological understandings of reciprocity. In Celtic mythology, the goddess Bóinn’s spirit became the River Boyne, giving it associations with poetry, fertility, and wisdom.

Restoring riparian buffers and ecological corridors can enable rivers to function as autonomous living systems within interconnected landscapes. Healthy rivers create natural pathways for wildlife, filter our water, and stabilise our climate. With ecological renewal, interdisciplinary collaboration, and creative engagement, they canal so provide us with spaces for reflection, imagination, and belonging.

If a river could speak, it might remind us that every act of care or neglect upstream reverberates downstream and that stewardship begins with attention. To listen to rivers is to acknowledge our shared dependence within a living system.

In this article – timely, in light of recent flood events – Phoebe Brady and Sarah Doheny argue that integrating environmental resilience with public amenity and treating rivers as living stakeholders, rather than as elements of infrastructure, is essential if we are to ensure the survival of our watercourses and our ecology.

Read

Three seemingly unrelated stories caught my eye in the news in recent months. In the Dublin suburb of Dundrum, residents spoke out in opposition to a proposal to build an “aerial delivery hub” in the centre of the town.[1] A meeting organised by local politicians was attended by the chief executive of the drone company, but this wasn’t enough to convince the citizens of Dundrum that the new hub was a good idea.

A few weeks earlier, Irish billionaire businessman Dermot Desmond was reported as having described the long-awaited Metrolink project as obsolete and “a monument to history”.[2] He argued that autonomous vehicles operated by artificial intelligence would make the rail line redundant, would cut the number of vehicles on the road dramatically, and eliminate congestion. His argument was dismissed by transport experts and citizens alike.

More recently, in the annual scramble for housing, students in Galway spoke in despair about the lack of available accommodation, noting that there are currently over 1,000 properties listed on Airbnb for Galway, while there are only 111 properties to rent on Daft.ie (in fact, the figure maybe below seventy).[3]

What these three stories have in common is that they are all underpinned by technologies which aim to minimise social interaction within our cities, based not on a desire to provide a service to society (whatever their proponents might claim), but to extract maximum profit by eliminating the cost of people doing real work.

Canadian writer Cory Doctorow coined the term “enshittification” in 2022 to describe how online platforms switch from serving their users, to serving their business customers at the expense of their users, to finally serving only their shareholders, resulting in a poor service that both users and business customers are locked into. A similar process can be observed in the way technology is used to deliver services in our cities.

Airbnb is an undoubtedly useful platform for people looking for short-term accommodation for city breaks and holidays. When it was founded in 2008, it was celebrated as a means to connect individual travellers with homeowners who had space to spare, allowing users to bypass overpriced hotels and find affordable accommodation. On the face of it, this seems like a worthy endeavour, helping to connect people and to make more efficient use of available accommodation.

Fast forward seventeen years, and the impact of Airbnb on housing availability and on mass tourism is causing a backlash in cities across the globe. Barcelona plans to ban short-term rentals from 2028 in response to a housing crisis that has priced workers out of the market. New York City has introduced laws to restrict short-term lettings and block non-residents from letting out properties. Restrictions are also in place in Berlin, Lisbon, and Athens. Elsewhere, short-term lettings are highly regulated to limit over-tourism. Rather than connecting people, the rise of short-term letting has resulted in a sterilisation of parts of our urban centres where key-boxes proliferate and visitors never physically meet their hosts.

The plan for drone deliveries is just the next stage in a progression from takeaway restaurants doing their own deliveries, to online delivery platforms operating from dark kitchens. Again, it comes from a worthy pretext – to help restaurants connect with their customers and to make ordering takeaway food simpler for customers – but in this case, the enshittification stage results in streetscapes where restaurants no longer have a public presence, but are attended by gig-economy workers who act as intermediaries between businesses and citizens. The drone delivery concept goes one step further, replacing that human intermediary with a machine. The citizens of Dundrum certainly don’t see how that transaction is of benefit to them.

A similar progression can be seen from the redesign of our cities to suit the private motor car and the well-documented impact that has had on social interactions in the city, to the proliferation of ride-hailing apps, and now the notion that AI-powered driverless cars are the future of urban transport. Though the ride-hailing apps promised an end to congestion and reduced car ownership, the reality was very different – more congestion and more cars – and any system of AI-powered driverless cars will be governed by the same commercial imperatives to increase car miles on city roads. Again, where, in this, is the benefit to citizens?

A city is a community of citizens. At its core, it exists for the people who live there, and it thrives on social interaction. But what these technologies are doing, or proposing to do, along with things like self-service check outs, dark kitchens, and co-living units (which, despite their name, are fundamentally isolating environments), is to strip away that core. Removing human interaction in the name of efficiency and cost effectiveness is ultimately to the benefit of shareholders rather than citizens.

The Dublin city motto, “Obedientia Civium Urbis Felicitas” (Happy the city where citizens obey), has come in for some criticism recently. The Dublin InQuirer newspaper ran an unofficial poll earlier this year to choose a new, more appropriate motto for the modern city, and the winning entry changed just one word – “Participatio Civium Urbis Felicitas” (Happy the city where citizens participate).[4] That participation should be not just in the democratic functions of the city, but in the life of the city, in the culture of the city, and in the community of the city.

As we are assailed with technological solutions purporting to improve the lives of citizens, let’s consider them through the lens of the happiness of the city and its citizens. This is not a rejection of technology, but an acknowledgement that ultimately, technology should serve the citizens. If our cities are to thrive into the future, let’s recognise the importance of participation and prioritise measures that encourage social interaction and build social cohesion.

Ciarán Ferrie makes the case for more citizen participation in city life, culture, community, and democracy.

Read

Our bodies do the work, do we think of them when they are working?

Feet ache from standing, backs tire from lifting, shoulders ache from poor posture at a desk. We sit down, stand up, take a break, take refreshment. In some workplaces, there is consideration of the worker and their body: canteens are provided, bathrooms are kept clean, and the ergonomics of a desk are contemplated. All of this relies upon the acknowledgement of, the visibility of, certain types of work and workers. If we turn our attention to the city as a workplace – specifically, the streets, thresholds, parks and pavements that make up the public realm in the city and that act as a place of work for many workers – how does it accommodate the bodies of workers? Is it hospitable?

Over time, the perceived value of certain types of work, and consequently certain types of workers, has fluctuated. When seen as essential to the economy, to growth, the needs and availability of workers are considered, and their ability to advocate for better working conditions is strengthened. This has occasionally resulted in an architecture that responds directly to workers’ needs. We might take the example of pithead baths, communal bathing facilities that were built close to coal mines in the early twentieth century. Here, miners could change and bathe; the dust and dirt of the colliery becoming the responsibility of the mine itself and not the worker and their home. In Architecture and the Face of Coal: Mining and Modern Britain, by Gary Boyd, we follow the development and eventual obsolescence of this distinctive typology, pointing to the transitory nature of coal mining as one of the reasons for the short lifespan of the baths and for their fading from view in histories of modernist architecture in Britain.[i] So we have an example of an architecture that springs up in response to workers’ needs, but that also mirrors the changing status of the workers themselves.

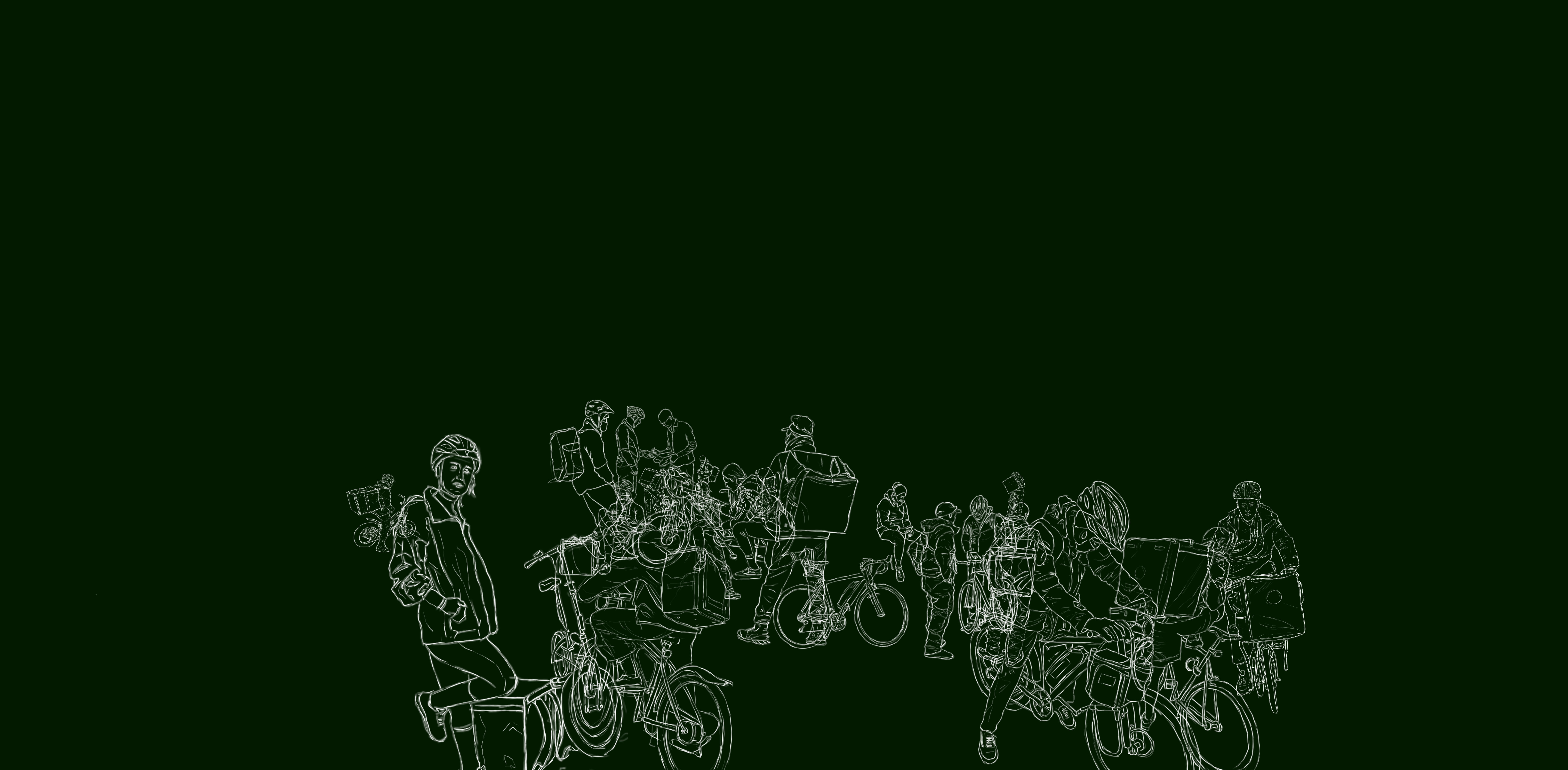

The value of different types of work is something that we continue to grapple with and that contributes to inequality locally and globally. Precarity is widespread.[ii] Nowhere is the daily reproduction of the worker more difficult and given less consideration than in the city workplace. A conspicuous example of precarious and disembodied labour is the fleet of food delivery riders that has grown in response to the evolution of online delivery platforms. This new virtual infrastructure has resulted in, but takes no responsibility for, a workforce that is reliant on the fabric of the city. While there has been recent media coverage of the riders' problematic working conditions,[iii] there has been less discussion about the pragmatic and bodily realities of their work, where they contend with weather, traffic, criminality and so on.

In The Practice of Everyday Life, historian and cultural theorist Michel de Certeau sets out a model whereby power structures are discernible by the “strategies” of agencies and institutions, representatives of the state or of commercial interests; the organising logic of city planning, for instance, or the virtual frameworks that map, track, and influence. Against, or within, these strategies are the “tactics” of the other; the citizen, the customer, or, to employ de Certeau’s preferred term, the user.[iv] If we pay close attention to the city workplace, we start to see the “strategies” and “tactics” at play, the creative and opportunistic ways of “making do” that individual riders employ in their everyday life: they rest against walls and railings; they take shelter under canopies and in ad hoc repair shops; they take shortcuts, crosscuts over rainslick tracks or in the narrowing gap between a bus and a van; they take risks;[v] they sit on park benches and at the feet of statues.

At O’Connell Monument:

Do you eat your lunch here?

“Yes, this is my office chair.”[vi]

A warehouse on Henry Place holds a rental and repair shop, renting primarily to food delivery workers. The building is a protected structure that is decaying as it awaits a contested redevelopment.[vii] A single open space is divided into two zones by a low plywood barrier: public (for rental) and private (for repair). Bikes stand ready. Metal shelves along the east wall hold the accessories that might be required by a rider. In front, a desk where forms are filled and rent is paid. In a corner, some sofas face a TV screen. A fridge, microwave and kettle provide basic facilities.

On Henry Place:

Do you take a break here?

“Yes, this is the only place that we are able to eat because we rent the bikes here, so they let us use the microwave, the refrigerator... This is the only place in the city that we can have a little space together to eat something.”

On this backland site, a temporary and informal responsiveness is demonstrated. The city user improvises on the ground, while elsewhere, a debate rages about value. In contrast to the windowsills and kerbstones that are often places of momentary rest for a delivery rider, a dilapidated and impermanent structure gives a sense of shelter and retreat, making space for camaraderie and some degree of bodily comfort.

On O’Connell Street:

Do the delivery companies provide any equipment or clothes for you?

“Not exactly, once in a while they give something for free, like the bag and the jacket, but not all the time. The jacket is more for promotion; it gets wet, you get wet anyway. We have to be careful because we can get sick most of the time, because the rain makes our bodies very cold. We have to be extra careful when it’s wet.”

Where previous communities of workers had their needs considered, as in the construction of pithead baths for miners, for example, it was possible to point to a single employer with responsibility for the welfare of their workers. Groups of workers could agitate and negotiate for facilities, for practical solutions to tangible problems. Emerging from a pit with body and clothing covered in black coal dust led to straightforward questions about washing, changing, eating dinner, and storing clothes during the working day. Improvements in conditions for miners were realised because these workers were together, situated, and visible. Another historical example of situated workers’ facilities was the series of green huts built by the Cabmen’s Shelter Fund in late-nineteenth-century London. The shelters provided hot drinks and food, a place to read the paper for cab drivers, answering a series of pragmatic, corporeal needs. Like many Victorian philanthropic efforts, they came with an undertone of self-serving paternalism. Now with a protected conservation status, a handful of shelters are still in use, the interiors remaining the exclusive preserve of cab drivers.

Today, in corporate[viii] settings, the body is considered in great detail. Ergonomic assessments are exacting in their appraisal of a body at a desk: the length of shin (footstool), the height of eye (monitor stand), the reach and range of forearm (vertical mouse). Training is provided in how and what to lift. In theory, an employer is responsible for assessing these risks to the body regardless of the location of their employee. But in an era of modern piecework, who cares for the pieceworker? And is there a parallel between the hands-offishness of employers and our attitude to city streets and passageways?

Delivery riders are visible in the city but untethered, distributed through the network of the streets, finding their own informal gathering places. They are not employees; they are independent contractors. This status allows them to be light-footed within a network of regulations and legalities.[ix] The subcontracting of accounts with various delivery companies, for instance, results in a grey market of official and unofficial riders. These tactics have their mirror in the ways in which riders improvise occupation of streets and pavements, and act, to a degree, on the city; they are limited, however, in how they might shape the city to their needs.

Emerging from a tradition that prioritises urban commerce and suburban living, we plan for the street as a thoroughfare, an artery, thinking mostly of flow, of efficiency. There is arguably a parallel prioritisation of the commuter worker within the workforce. Certain dimensions are assigned for cars and buses, for bicycles and pedestrians to move seamlessly from the city centre to the periphery. This diminishes the value of the urban realm as a place to be, to dwell. What if we were to see (or return to) the streetscape, the weather-world[x] of paths, gratings and doorways, of tarmacadam and streetlights, as a single, integrated space that hosts diverse needs and functions, including those of city workers? The sense of the city as a place to move through can be challenged by an ambition to make a hospitable city: a place of rest, shelter and conversation. Acknowledging the public realm as a workplace might prove a catalyst for an inclusive approach to city-making, considerate of all bodies and all work.

Our bodies do the work. In this article, Anna Cooke asks: do we think of them when they are working?

ReadWebsite by Good as Gold.